INTERNAL CAMP RESISTANCE

From the first days of the existence of the Perm political camps, a constant struggle took place between the prisoners and the camp administration, which did not cease until the last political prisoners were released.

The administration violated the few rights that prisoners had, while political prisoners fought for the observance of these rights and also for the common civil rights of people at liberty. Although the camps were under the jurisdiction of the Interior Ministry, they were in fact run by the KGB: it was KGB officers who ordered which prisoners should be persecuted and which should be spared. Years after the camp was closed, when one of the former camp controllers – the official name for the wardens – heard a former prisoner saying “That time I was put in the punishment cell for nothing”, he said indignantly: “What do you mean, for nothing? A KGB officer ordered it!”

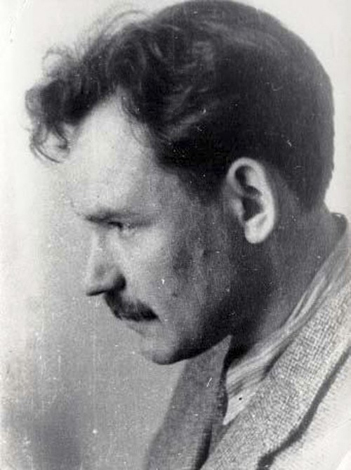

Photo: political prisoner Yevgeny Pronyuk. In defense of his rights and the rights of all prisoners to meetings, several dozen political prisoners in the Perm-35 camp held a month-long hunger strike in May-June 1964. One of the most famous Soviet political prisoners was Vladimir Bukovsky. For organizing a collective hunger strike in defense of Yevgeny Pronyuk he was transferred to a penitentiary regime at the Vladimir prison.

Motives for punishing prisoners were easily found: “for infringement of clothing regulations” – for not fastening the top button, although most prisoners lined up for inspection had unfastened buttons; “for non-fulfillment of production tasks”, although prisoners rarely fulfilled these tasks. The arsenal of official punishments was not large: extra work duty, deprivation of access to the prison shop, deprivation of correspondence, deprivation of meetings, but they were all used actively. And the duty for maintaining the camp fences and renovating the SHIZO itself was an utterly cynical punishment that never failed to ensure that prisoners were sent to the SHIZO or PKT cells, as political prisoners categorically refused to do this work – “a prisoner does not build his own prison!”

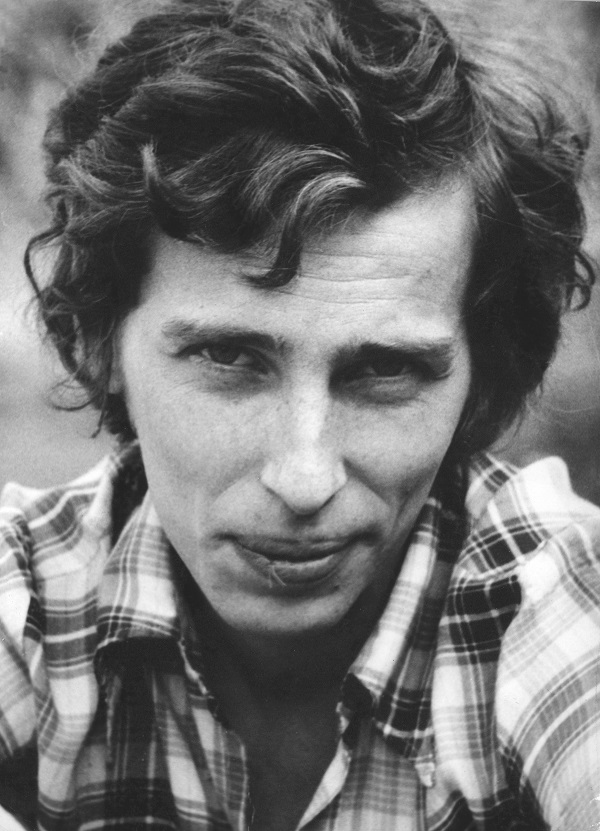

Photos: political prisoners Valery Marchenko, Ivan Svetlichny and Semyon Gluzman. In the Perm-35 camp, and later in the Perm-36 camp, they organized a regular collection of information on violations of prisoners’ rights and sent it outside the prison, and initiated many actions of resistance by political prisoners.

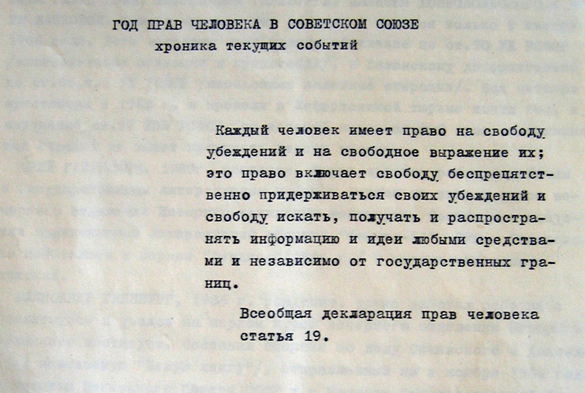

The title page of the bulletin “Chronicle of Current Events”, where information about violation of prisoners’ rights was published

The forms of possible resistance were also not particularly varied – official appeals and complaints to supervisory and other official channels, which the prisoners used as much as they could. Some of the numerous complaints reached their addressees, some even led to inspections, some were remembered and could be recalled in career appointments… This is how prisoners insured that controllers and officers were forced to address them as stipulated by law, using the polite form of you, “Vy”. This rule was not observed anywhere except in political camps!

Besides complaints and appeals, there were only work strikes and hunger strikes, and reports about them and the causes for them constitute the main bulk of information secretly sent out of the camps and cells to the “Chronicle of Current Events” and other human rights publications.

Photo: political prisoner Ivan Kovalyov, son of dissident and political prisoner Sergei Kovalyov. In the Perm-35 camp, for defending the rights of prisoners not to be punished for unintentional non-fulfillment of the work norm, he spent 391 consecutive days in the SHIZO and PKT, and over 500 days in total.

Work strikes and hunger strikes were both individual and collective – the latter, which were especially severe and painful, and sometimes even fatal, were the most effective. If it had not been for these hunger strikes, the authorities would have soon made the prisoners knuckle down; collective work and hunger strikes were the basis of a certain balance tolerated by both sides between the camp administration and the prisoners. The extreme form of resistance was when prisoners practically switched to a political regime: they removed the name tags from their clothes and refused to do any work or carry out the orders and instructions of the administration. Of course, they were immediately sent to the SHIZO on a punishment ration – a hot meal once every two days.

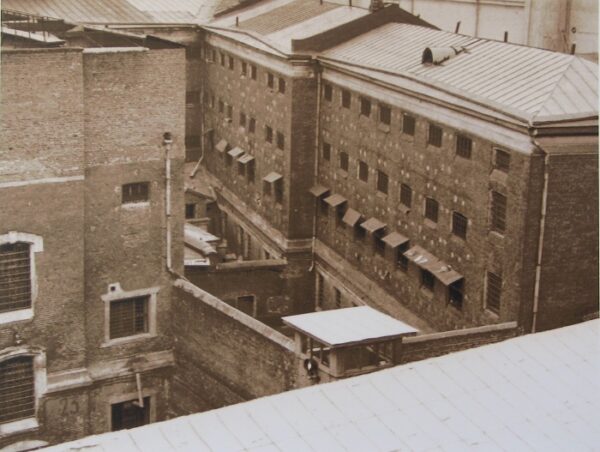

Especially unruly prisoners could expect a new, “people’s” trial in the town of Chusovoy and a ruling to move them to a penitentiary regime, and then to the cells of the Vladimir or Chistopol prisons. 52 people were moved from the Perm political camps to the penitentiary regime.