Vasily Vasilyevich Ovsienko walked along the barracks of the special regime area, prying on the rags and garbage left over from the abandoned camp with his toe. A year ago, in 1988, he was here in the status of a “convict”: he was the so-called “repeater” or “political recidivist”, that is a person who was repeatedly convicted under the criminal article “Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.”

The first time he was imprisoned under this article was in 1973 – for writing to the Central Committee of the CPSU and “prominent people of the Soviet Union” about political repressions in Ukraine, and participating in the publication of the “Ukrainski Vestnik”. He served four years in Mordovia. Then, in 1979, there was an instigated case of an attack on a policeman, which ended in three years in prison. And right there, in the camp, in 1981, there was a new “political” trial: he was charged with the article “Instead of the last word” and a letter about the situation of prisoners sent from the zone to the UN. This is the second part of the infamous article 62 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR – “Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda by a person previously convicted of especially dangerous state crimes.” This means that the status of a “especially dangerous recidivist”, imprisonment in a special regime zone for 10 years and a subsequent exile for 5 years.

So the barracks through which Vasily Vasilyevich was walking now was familiar to him. Too familiar. Particularly unbearable conditions were created for political prisoners in it: moral and physical torture, beatings – moreover, by criminals who were specially planted in cells for dissidents. It was there, in the working zone of the special regime of the Perm-36 camp, that Balis Gayauskas, a fighter for the independence of Lithuania, received his 9 stab wounds. It was there, in the punishment cell, that the great Ukrainian poet Vasil Stus died in 1985 after a hunger strike. Vasily Ovsienko returned to the places where the last nightmarish seven years of his life had passed to take the body of Stus out of the abandoned zone to rebury it with honors in his homeland, in Ukraine.

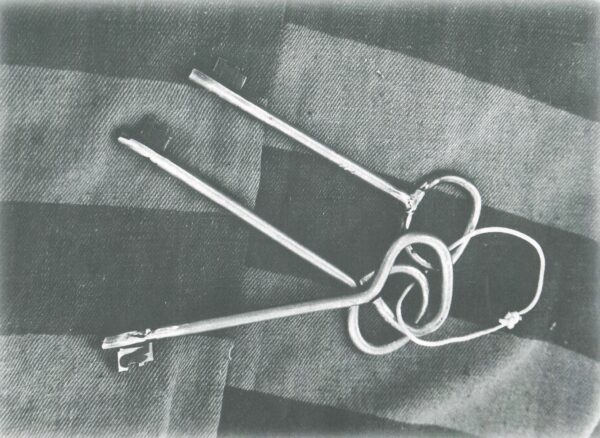

Yes, in the wake of perestroika in 1988, the political zone was closed, and all its inmates were released by pardon. The dissidents could not wait for the recognition of mistakes, or on the apologies from the Soviet authorities, who first imprisoned and then “pardoned” them. But anyway, it was freedom. And Vasily Vasilyevich now walked through the terrible place not under escort, not under the roar of locked bars, but as a citizen of his country. And then on the floor, among the garbage, he saw a bunch of keys. The same keys that locked the cells in the cold barracks, and the gateway gate, where the humiliating “shmon” took place every day, and the punishment cell, from where people sometimes did not return alive. Rusty keys lay underfoot as a symbol of a time thrown back forever. Vasily Vasilyevich picked up the bundle and took it to Kyiv, transferring it to the fund of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine.

On September 5, 1995, when the Perm-36 Memorial Museum of the History of Political Repressions opened in this very barrack of the former political camp, Vasily Ovsienko, of course, was one of the guests of honor. And his gift to the fund of the newly created museum was a copy of those keys. He made it and brought it from Kyiv, realizing how important this artifact would be for the collection and for the history of Perm-36. Well, after 2014, which was marked by a raider seizure of the funds of the public museum by the regional Ministry of Culture, this bunch of keys became one of the few miraculously surviving exhibits, since at that moment it was exhibited outside of Kuchino.

Unfortunately, there is no certainty that the collection items left in the care of the new administration of the museum complex will have a happy fate. According to Tatyana Georgievna Kursina, the conditions for their storage were already catastrophic in 2019: the exhibits were stored in a very damp and ventilated lock room with an earthen floor, without heating, near the confluence of two rivers – Boyarka and Chusovaya. Therefore, the value and significance of these few items left in the hands of the public museum team increases every year. And a bunch of keys from the special regime barracks is one of them.