The largest group of prisoners of the Perm political camps, numbering 348 people, were those whose sole or primary charge determining the measure of their punishment was “agitation or propaganda conducted with the aim of undermining or weaking the Soviet regime or committing individual particularly dangerous crimes against the state, spreading slanderous lies defaming the Soviet state and public system, and also spreading or preparing or storing for these goals in written, printed or other form works of this content.”

This charge was introduced by the USSR Law “On criminal liability for state crimes” of 25 December 1958, and included in the new criminal codes of all republics of the USSR, coming into effect in 1961. Some prisoners were also charged under the previous article of “propaganda or agitation containing calls for overthrowing, undermining or weakening the Soviet regime, or carrying out individual counter-revolutionary crimes, and also distributing, preparing or storing literature with this content,” according to the criminal codes in force until 1959.

The largest group among the “anti-Soviet prisoners” (91 people) were sentenced on individual charges of committing various acts classified by the investigations and trials as “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”. The specific charges against them may be divided into several sub-groups, while a number of prisoners were incriminated on several of these charges, such as writing “anti-Soviet” books, articles or poems and distributing samizdat; distributing leaflets and listening to foreign radio stations broadcasting to the Soviet Union; writing and sending “anti-Soviet” letters and “verbal statements of an anti-Soviet nature” etc.

The second largest category included 45 prisoners sentenced for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in group court trials, or in individual trials, but for participation in group actions, who were not charged with “organized activity, directed towards preparing or carrying out highly dangerous crimes against the state, for creating an organization with the goal of committing these crimes, and also participating in an anti-Soviet organization”. The groups were usually small: there were 17 groups of two people and seven groups of three people. Five prisoners were sentenced in individual trials as heads of groups which were not declared to be anti-Soviet, but which were not officially registered or permitted by other means, so they were regarded as unlawful: four of them were religious groups, and one was an educational and cultural group. Only one group, the Leningrad “Communists’ Union”, had five members.

The list of “anti-Soviet prisoners” of Perm political camps should also include 30 prisoners who were sentenced on charges of treason without being charged with anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. This usually concerned heads or leaders of organizations, whose other members were sentenced on charges of anti-Soviet agitation, and also several dozen “nationalists” and escapees from the USSR whose sentences included anti-Soviet agitation.

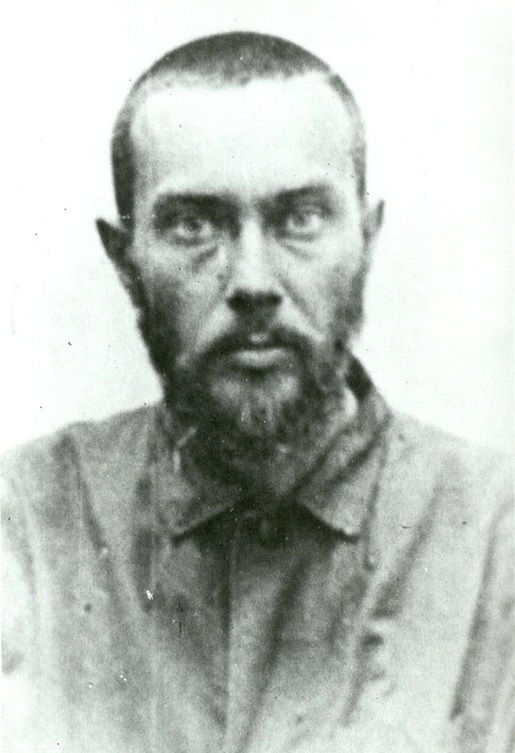

Photo: Igor Ogurtsov, sentenced in 1961 to 15 years in prison on charges of treason and creating the anti-Soviet organization “All-Russian Social-Christian Union of People’s Liberation”. 17 members of this union were sentenced on charges of anti-Soviet agitation.

Photo: Lev Lukyanenko, sentenced in 1961 to execution on charges of treason for creating the anti-Soviet organization “Ukrainian Workers’ and Peasants’ Union”, mitigated to 15 years in prison.

297 of the 378 prisoners charged with anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda and serving their sentences in Perm political camp were sentenced after the creation of the Perm political zone. And these camps were created specifically for them. Over a third of the anti-Soviet prisoners were human rights defenders or people with similar values who sympathized with them, helped them and became active human rights defenders themselves while in prison.

Photo: Sergei Kovalyov, dissident, human rights advocate, member of the Initiative group for protection of human rights in the USSR (from 1969), editor of the human rights bulletin “Chronicle of Current Events” (1972-1974).

Perm political camps were created for the maximum possible isolation of prisoners, but human rights defenders found methods of sending information about the situation in the camps out into the wider world. The most reliable and effective method, but also the most difficult and unpleasant, was to pass on notes during long meetings – up to three days – between prisoners with relatives, when security guards locked them up in in special meeting rooms. As the prisoners and their relatives were thoroughly searched and examined, and even gynecologists searched the women, the notes could only be carried by swallowing them. The notes were wrapped around matches and sealed in several layers of plastic film. Several layers were required so that the upper layer could be torn off when the note was excreted, and then swallowed again. In this way, information was sent to the outside world about dozens of alarming incidents taking place in the camps: this news was published in samizdat, sent abroad and returned to the USSR in broadcasts by foreign radio stations in various languages of the country. The truth was revealed to the world.

Photo: note in Armenian, which was never sent out of the prison. Discovered during restoration of the barracks in the Perm-36 camp.

Human rights defenders in Perm political camps were not only irreconcilable fighters for prisoners’ rights, primarily prisoners who refused to work and declared hunger strikes, but also the main initiators of collective protests – strikes and hunger strikes which other prisoners took part in. The mass protest forced the camp administration at least partially to satisfy protestors’ demands. Human rights defenders upheld the dignity of all prisoners of political camps whose rights were violated, including those sentenced on charges connected with the Second World War.