балабанова

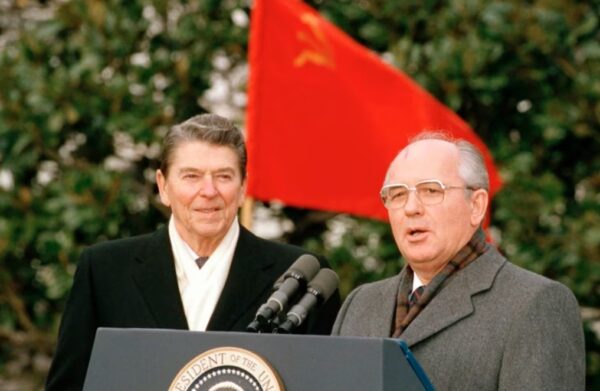

In October 1985, Ronald Reagan met for the first time with Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva, where they discussed the need to curtail the arms race and limit strategic and nuclear weapons. At the end of the meeting, Reagan mentioned human rights and political prisoners in the USSR – like his predecessor Jimmy Carter, he had made these issues part of his election campaign. Gorbachev exploded: “I’m not your pupil, Mr. President, and you’re not my teacher!”

In February 1986, Gorbachev announced in an interview with L’Humanité: “…concerning political prisoners. We do not have them in our country… we do not persecute citizens for their convictions.” But at the meeting between the leaders of the USA and the USSR held in Reykjavik on 11-12 October of the same year, the issue of political prisoners and human rights was officially placed on the agenda. In subsequent months, departments of human rights were formed under the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On 28 November 1986, Anatoly Marchenko, who was serving his sixth prison sentence, stopped a hunger strike after 117 days, which he had begun with the demand to release all political prisoners. He had previously spoken with a representative of the Communist Party, who had flown specially to the Chistopol prison. But the hunger strike had seriously damaged Marchenko’s health, and on 8 December he died. On 16 December, Gorbachev called Andrei Sakharov to inform him that he had been released from his exile in Gorky.

In early February 1987, the release of political prisoners began, and continued for 20 months. All prisoners whose main charge was anti-Soviet agitation was released from the Perm and Mordovian political camps, and also from exile. Initially, their release was dependent on amnesty, requiring a personal, written petition by the prisoner. This meant confessing to the crimes, and recognizing the lawfulness of the trial and the justice of the sentence. Far from all political prisoners were prepared to make this confession. Those who refused were then told: “If you don’t want to request forgiveness, at least write something”. But eventually they were all released without even this requirement.

The last political prisoner sentenced for anti-Soviet agitation, Bogdan Klimchak, was only released on 11 November 1990. The main charge in his sentence was treason – he had tried to flee the country. He was also carrying several dozen pages of “anti-Soviet and slanderous documents”, mainly of his own composition. The schedule and procedure for releasing the political prisoners were undoubtedly controlled by the KGB.

The mass release of political prisoners meant that all the political prisons of Mordovia, and also the Perm-36 and Perm-37 camps, were almost empty by the end of 1987. The prisoners remaining, mainly sentenced on charges for treason – collaboration, attempting to flee the USSR, espionage and revealing state or military secrets – and also anti-Soviet prisoners who the KGB were for some reason reluctant to release, were gathered together in the Perm-35 camp. The last “traitors” were released from this camp on 7 February 1992.

After the release of the highly dangerous state criminals, the Mordovian political camps and the Perm-37 camps were reformed in 1988 into conventional criminal corrective labor camps, and the Perm-36 camp was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Perm Oblast department of social welfare to house a neuropsychiatric care home.

INTERNAL CAMP RESISTANCE

From the first days of the existence of the Perm political camps, a constant struggle took place between the prisoners and the camp administration, which did not cease until the last political prisoners were released.

The administration violated the few rights that prisoners had, while political prisoners fought for the observance of these rights and also for the common civil rights of people at liberty. Although the camps were under the jurisdiction of the Interior Ministry, they were in fact run by the KGB: it was KGB officers who ordered which prisoners should be persecuted and which should be spared. Years after the camp was closed, when one of the former camp controllers – the official name for the wardens – heard a former prisoner saying “That time I was put in the punishment cell for nothing”, he said indignantly: “What do you mean, for nothing? A KGB officer ordered it!”

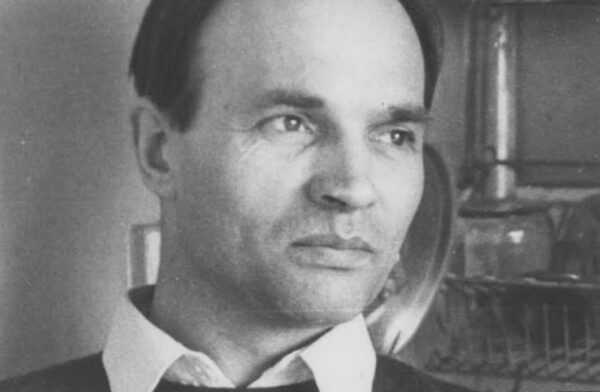

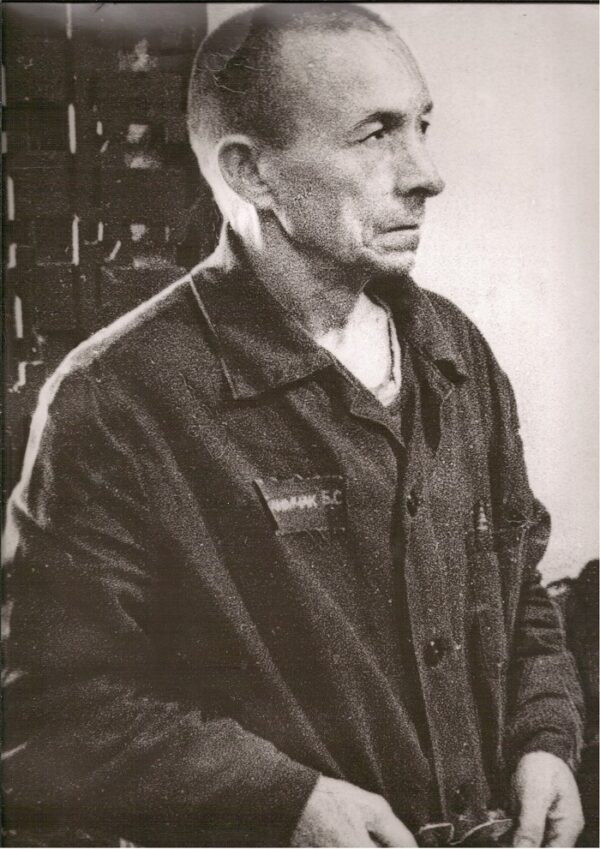

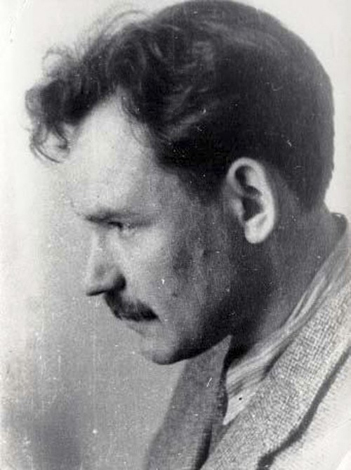

Photo: political prisoner Yevgeny Pronyuk. In defense of his rights and the rights of all prisoners to meetings, several dozen political prisoners in the Perm-35 camp held a month-long hunger strike in May-June 1964. One of the most famous Soviet political prisoners was Vladimir Bukovsky. For organizing a collective hunger strike in defense of Yevgeny Pronyuk he was transferred to a penitentiary regime at the Vladimir prison.

Motives for punishing prisoners were easily found: “for infringement of clothing regulations” – for not fastening the top button, although most prisoners lined up for inspection had unfastened buttons; “for non-fulfillment of production tasks”, although prisoners rarely fulfilled these tasks. The arsenal of official punishments was not large: extra work duty, deprivation of access to the prison shop, deprivation of correspondence, deprivation of meetings, but they were all used actively. And the duty for maintaining the camp fences and renovating the SHIZO itself was an utterly cynical punishment that never failed to ensure that prisoners were sent to the SHIZO or PKT cells, as political prisoners categorically refused to do this work – “a prisoner does not build his own prison!”

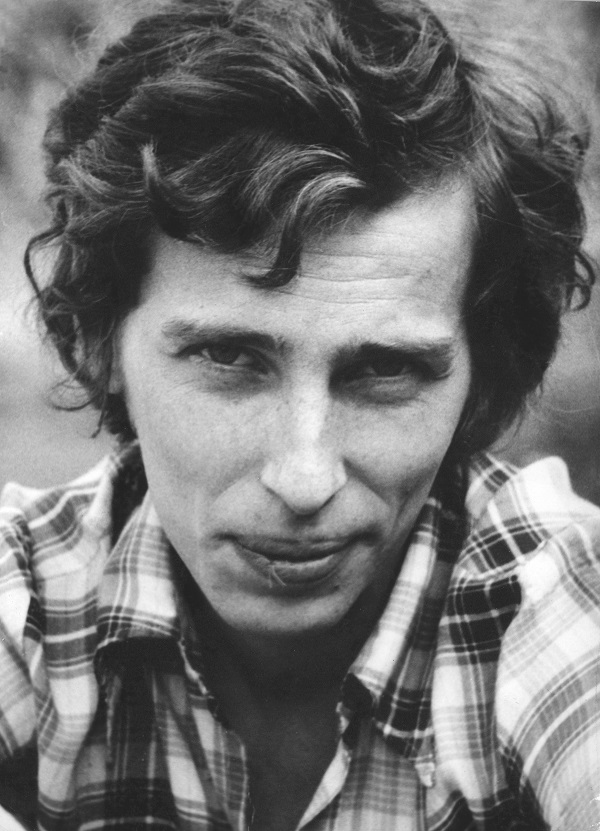

Photos: political prisoners Valery Marchenko, Ivan Svetlichny and Semyon Gluzman. In the Perm-35 camp, and later in the Perm-36 camp, they organized a regular collection of information on violations of prisoners’ rights and sent it outside the prison, and initiated many actions of resistance by political prisoners.

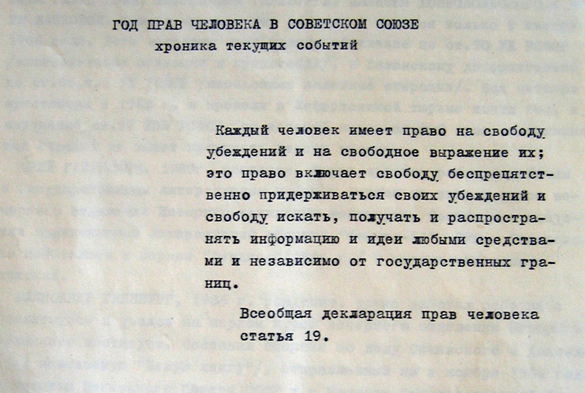

The title page of the bulletin “Chronicle of Current Events”, where information about violation of prisoners’ rights was published

The forms of possible resistance were also not particularly varied – official appeals and complaints to supervisory and other official channels, which the prisoners used as much as they could. Some of the numerous complaints reached their addressees, some even led to inspections, some were remembered and could be recalled in career appointments… This is how prisoners insured that controllers and officers were forced to address them as stipulated by law, using the polite form of you, “Vy”. This rule was not observed anywhere except in political camps!

Besides complaints and appeals, there were only work strikes and hunger strikes, and reports about them and the causes for them constitute the main bulk of information secretly sent out of the camps and cells to the “Chronicle of Current Events” and other human rights publications.

Photo: political prisoner Ivan Kovalyov, son of dissident and political prisoner Sergei Kovalyov. In the Perm-35 camp, for defending the rights of prisoners not to be punished for unintentional non-fulfillment of the work norm, he spent 391 consecutive days in the SHIZO and PKT, and over 500 days in total.

Work strikes and hunger strikes were both individual and collective – the latter, which were especially severe and painful, and sometimes even fatal, were the most effective. If it had not been for these hunger strikes, the authorities would have soon made the prisoners knuckle down; collective work and hunger strikes were the basis of a certain balance tolerated by both sides between the camp administration and the prisoners. The extreme form of resistance was when prisoners practically switched to a political regime: they removed the name tags from their clothes and refused to do any work or carry out the orders and instructions of the administration. Of course, they were immediately sent to the SHIZO on a punishment ration – a hot meal once every two days.

Especially unruly prisoners could expect a new, “people’s” trial in the town of Chusovoy and a ruling to move them to a penitentiary regime, and then to the cells of the Vladimir or Chistopol prisons. 52 people were moved from the Perm political camps to the penitentiary regime.

Doctors in the Soviet Union did not give the Hippocratic oath. But they did give the oath approved by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR, which included the words: “…I solemnly swear: to devote all knowledge and efforts to protecting and improving human health…”

Information from the human rights bulletin “Chronicle of current events” (CCE):

“The medical commission removed the invalid status from the prisoner, the Lithuanian Kurkis, who was doing a 25-year sentence. Kurkis suffered from an ulcerous disease and had not worked for many years. After the commission’s decision, he was sent to do hard labor – to plough “no-man’s land”. In the first day the ulcer ruptured. The head of camp No. 35 Pimenov called lieutenant colonel T. P. Kuzntesov in Perm (the surgeon of this camp); he refused to make a call, saying the weather was bad. Kurkis died”

CCE, issue 30, December 1972

Medicine is perhaps the most horrible and shameful thing that existed in the Perm political camps. The actions of the surgeon Kuznetsov were no exception, but rather the rule. The Chronicle of Current Events alone contains over 10 reports on the deaths of prisoners caused by refusing or delaying medical assistance. And how many deaths were not mentioned in the chronicle, and not noticed by anyone at all?

Every political camp had its own medical unit, and the Perm-35 camp had a two-storey hospital for all three of the political camps, which had been built recently and had all the necessary equipment. The hospital was always fully staffed with medical personnel. The camp medics were paid a considerable extra salary for the “hazardous nature” of their service, but of the almost 2,000 reports in the “Chronicle” about incidents at the Perm political camps, over 150 are connected with medical problems.

Some publications:

“10 people, including two with one leg, were found eligible for work by the medical commission. Many prisoners had their invalid status of many years removed. Lieutenant colonel of the medical service T.P. Kuznetsov was appointed chairman of the medical commission, who did not ask medical questions, but only asked: “What sentence? What charge?” The replies were sufficient to make a decision” – CCE, issue 30

“In the camp the prisoner Skobas died. Shortly before his death he went to see a doctor, but was not put in hospital ‘because there were no places’. He was doing hard physical labor,” CCE, issue 38.

“It was learned that the administration of the camp and the UKGB in Skalny asked head doctor Kuverden not to give prisoners exemptions from work, as the camp was not fulfilling the plan,” CCE, issue 42.

“S. Kovalyov went to the camp doctors requesting to be sent to the Leningrad hospital for prisoners, to have an operation. The head of the camp medical unit Petrov told Kovalyov: ‘We’ll treat you if you behave well,’” CCE, issue 42.

“The patient I. Ogurtsov was sent to work at the boiler room. The doctor Chepkasova initially exempted him from work, but then at the demand of the administration cancelled the exemption,” CCE, issue 51.

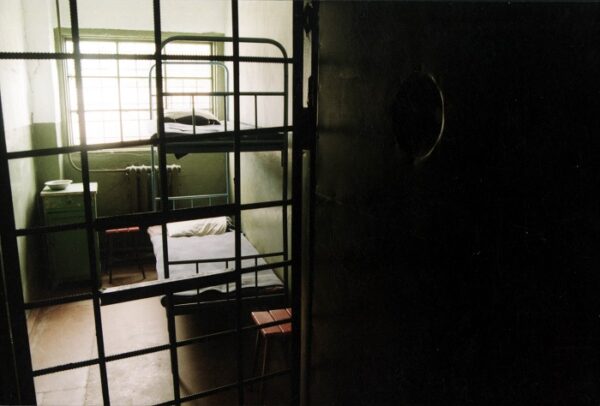

The SHIZO was one of the severest punishments for camp prisoners. In the maximum-security section, the only punishment more severe was being put in the chamber-type cell (PKT), and in solitary confinement in the special security section.

“For violating prison regulations, the following measures may be applied: a warning or reprimand; extra duty for tidying quarters and camp territory: deprivation of a meeting; deprivation of the right to receive a parcel or package and prohibition from buying groceries for a period of up to one month; cancellation of improved prison conditions; transfer to the punishment cell with or without being sent to work”

Article 53 of the Corrective labor code of the RSFSR, 1970

In the punishment cell, prisoners did not have matrasses or sheets, and they slept on bare boards of a fold-out bunk, which was fixed to the wall at 6 a.m. and taken down at 10 p.m. They were not taken out for walks, they were forbidden to smoke, they did not have books or newspapers, and they were not given letters they received.

The walls of the cell were covered in rough cement, a so-called “fur coat”. It was impossible to lean against them. Initially, the period of detainment in the cell was limited to 15 days, but a secret order of the USSR Interior Ministry No. 20 of 14 January 1972 permitted for this term to be extended with new orders for holding prisoners. The total period for holding prisoners in the cell was only limited by the state of their health. The PKT cells with the same fold-up bunks were different in that they had smooth walls, and at night prisoners were given matrasses and sheets.

“.., in the cell, in solitude: no books, no newspaper, no paper, no pencil. You’re not taken out for walks, or to the bathhouse, you’re fed every two days, there’s practically no window, there’s a lamp somewhere in a niche, in the wall, right by the ceiling, it barely illuminates the ceiling. There’s one hollow in the wall – your table, another is a chair, you can’t sit on it for more than ten minutes. Instead of a bed for the night you’re given a bare wooden board. You’re not given any warm clothing. In the corner there’s a slop bucket, or just a hole in the floor, which stinks all day. In short, it’s a cement bag. And smoking is prohibited. The dirt is eternal. There’s blood spattered across the walls, because tuberculosis patients are also held here. And so you start to sink beneath the water, to the very bottom, into the ooze. That’s what it’s called in prison: to sink into the cell, to rise from the cell.”

Vladimir Bukovsky “And the wind returns…”

“Persons moved to the punishment cell… to the chamber-type cell… and also to the solitary confinement cell receive food according to reduced norms,” – article 56 of the corrective labor code of the RSFSR for 1970. Meat and animal fats were completely excluded from their ration. If the prisoner in the cell did not work – if he refused to work himself or was put in the cell with the instructions “without being taken to work”, he received food based on the punishment norm established in 1939: one hot meal every second day, and every other day 450 grams of bread and 20 grams of salt. After a few days of this food, the smell of acetone appeared on the prisoner’s breath – the muscle tissues began to break up. International law has declared this norm to be torture by starvation.

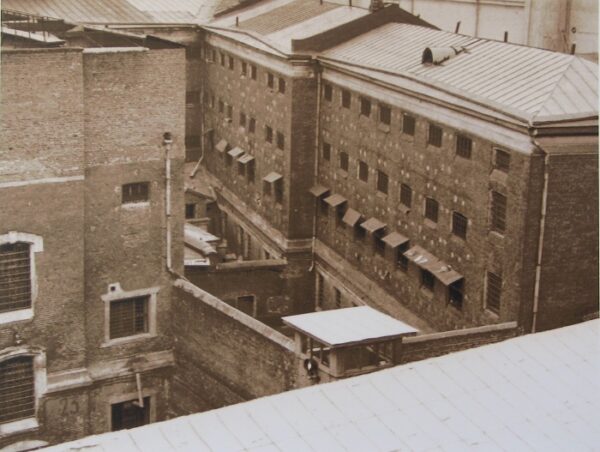

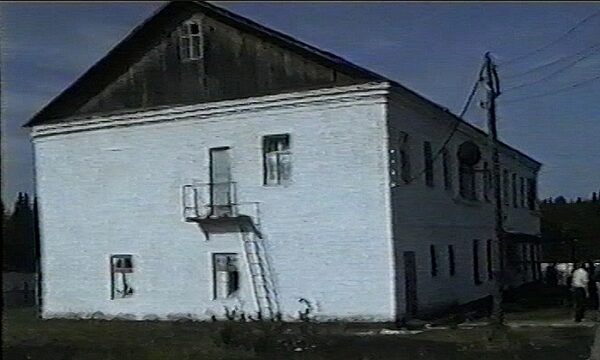

The SHIZO at the Perm-36 camp was especially harsh. The punishment cells and the chamber-type cells were in the same brick building built in the late 1940s, and were sometimes mutually interchangeable if necessary. The building was constructed in such a way that it was even cool during the July heat, and very cold in winter, while prisoners only wore a light cotton robe and slept on bare bunk boards painted with enamel.

The founders of the museum often heard people say: “Here even the old Lithuanians cried,” – the unbending Lithuanian partisans who grew old in the camp, serving their incredible 25-year sentences and preserving their dignity to such an extent that they refused to talk with the camp officers in Russian – but even they were unable to hold back the tears from the cold, pain and sense of helplessness.

As the requirements for maximum isolation at the Perm political camps did not allow prisoners to spend any time outside the camp territories, they had to work exclusively inside the camp perimeters. In the first months there were considerable problems in both camps in organizing work for the prisoners, but soon a solution was found when the camps received a contract for production work from industrial companies.

At the Perm-35 camp, the former sewing factory of the colony for underage offenders was re-equipped for sewing canvas bags to hold tools and spare parts for power saws manufactured at the Dzerzhinsky factory in Perm, and knitting netted bags for holding vegetables. In Perm-36, the workshops were equipped for manufacturing electronic components for irons manufactured by the Lysvensky turbine-generator factor. The majority of prisoners were employed at these workshops.

The manufacture of components for irons consisted of several operations for producing thermal electric heaters, contact panels and assembly of all components of the electrical circuit, which included the following steps: winding heating coils, placing the spirals and sand in copper tubes; packing the contents into tubes on the vibration bench; shaping the thermal electric heaters on the press; cutting contact panels out of the laminate, placing copper contacts in them; cutting screw threads in contacts; cutting metal components for the lightbulb; winding the resistance wire for the lightbulb; assembling all elements of the contact panel; final assembly of all components in a single chain, which was then delivered to the factory. In their memoirs, former prisoners wrote about how torturous this routine work was.

The production norms were exactly the same as they were at the factory itself, but prisoners rarely fulfilled them completely. Sometimes this was for physiological reasons – for example, not everyone could cut a screw of 3 millimeters in diameter or screw components and contacts with 3- millimeter bolts to panels, without special equipment and in a poorly lit room. But mainly it was because the work went against their principles. “We didn’t resist the Soviet regime to do this.” They usually only produced enough to avoid being punished “for non-fulfillment of the norm” by being placed in the punishment cell.

Besides manufacturing iron parts, several other metalworking and lathing works were carried out on commissions from companies, there was heavy labor at the sawmill and at the camp boiler room, work on repairing camp buildings, plowing the boundary strip and repairing camp fences. The last two tasks were primarily carried out by prisoners sentenced on charges of collaborationism and espionage, as political prisoners faithfully observed the old maxim: “a prisoner does not build his own prison”. Rather than doing this, they were prepared to go on hunger strikes, be put in the punishment cell and even face death.

In ordinary camp settlements there was always a great deal of work outside the camp zones, traditionally done by prisoners: repairs, new construction, auxiliary work etc. As political prisoners were not permitted outside the perimeter, every political camp had a so-called “small zone” for this purpose with ordinary criminals, some of whom were brought in specially. But the political prisoners never came into contact with them.

The life of prisoners in political camps was organized according to the corrective labor codes, standard rules of internal order and decrees of the USSR Interior Ministry. The daily routine for the Perm-36 camp stipulated eight hours of sleep, eight hours of work with a two-hour break for meals – these two hours included searching prisoners as they were moved from the work zone to the living zone and back, two hours for assembly for work and dismissal from work, again with a long search in moving from one zone to another, and two hours for political lessons and compulsory unpaid work to tidy and “improve” the territory.

Photo: renovated search building for transfer from the living zone to the work zone, during which all prisoners were searched at each transfer, four times each day. One search of a group of 80-100 prisoners took up to one hour: they were searched thoroughly, in groups of five; sometimes they had to take their clothes off and had the seams of their clothing checked, while the rest of the prisoners stood in formation in front of the building or behind it, no matter what the weather was like.

The secret decree of the USSR Interior Ministry of 14 January 1972 established additional restrictions for highly dangerous state criminals: all movements of prisoners, apart from the morning toilet and an hour of “private” time in the evening, were only allowed in groups, even at a distance of several dozen meters from the barracks to the canteen. Prisoners were prohibited from entering the rooms of other groups, were prohibited to wear beards, and the names of the prisoners and the numbers of their groups were printed on labels sewn to their clothing. Prisoners were obliged to remove their hats in front of camp administration employees.

The list of products permitted in packages and parcels was limited, and also the assortment of products and goods at the camp shop, censorships rules for correspondence were toughened, and the periods that prisoners were held in punishment isolation cells were increased.

When employees of the law-enforcement bodies sentenced on criminal charges were held in this camp, toilets were installed in the barracks

The daily norms for nutrition for prisoners were determined by a decree of the USSR Interior Ministry of 16 August 1958. The changes made to it later were insignificant.

| Bread of rye flour | 700 g | Combined fat | 4 g |

| Wheat flour of the 2nd sort | 20 g | Sugar | 15 g |

| Various grains | 110g | Salt | 20 g |

| Pasta | 10 g | Tomato paste | 5g |

| Meat | 50 g | Bay leaf | 0.1g |

| Vegetable oil | 15 g | Vegetables | 250 g |

This ration was the minimum sufficient to maintain vital activity: in political camps, apart from prisoners held in punishment isolation cells, the prisoners did not starve, unlike in the general prison camps, where groceries were often stolen. But they were constantly hungry.

“You couldn’t say that the hunger was particularly painful – it wasn’t severe hunger, but slow, chronic underfeeding. So you soon stopped feeling it very strongly, you just felt a monotonous pain, like a toothache. You even stopped realizing that it was hunger, and after a few months, you suddenly noticed that you found it painful and uncomfortable to sit on a bench, and at night, you felt something squeezing and pressing you – you shook the mattress a few times, and you turned from side to side, you felt uncomfortable. You feel as though your bones were sticking out of you. But you didn’t really care anymore. And you couldn’t get up abruptly from the bunk – your head would start spinning.”

Vladimir Bukovsky “And the wind returns…”

Constant annoyances were the tasteless food, the monotony of the ration and the lack of fresh vegetables – fermented, sour cabbage and dried potatoes was almost always used. Even in autumn. Prisoners tried to diversify the ration with wild grass growing in the camp territory, which often caused stomach upsets and poisoning, and some tried to grow edible herbs, but these plants were mercilessly stomped on. The food sometimes contained worms…

Another severe problem was the cold. In the winter the temperature in the barracks and workshop hardly ever rose above the level of 18 degrees, which was stipulated by the rules for internal order.

The entire life of the prisoners took place within the camp perimeter – they were never taken outside the camp fences. They were transported from camp to camp in closed vehicles – avtozaks. There was not enough color – everything around them was gray. The prisoner Lev Timofeev found a solution – he asked for colorful stamps to be placed on the letters sent to him. When the administration employees realized this, they started cutting the stamps off the envelopes.

“…Or you receive a colorful postcard from home and you keep staring at it like an idiot, it’s so amazing to see different unfamiliar colors than you can’t take your eyes off it.”

Vladimir Bukovsky “And the wind returns…”

In the special security corrective labor camps, men serve their sentences who have been declared highly dangerous recidivists, and men who had the death penalty mitigated to imprisonment under amnesty. The prisoners in the special corrective labor camps are held in conditions of strict isolations in cell-type rooms; they can go to buy groceries and essential items of a sum of up to four rubles a month; they have the right to one short and one long meeting in a year; they can receive not more than two parcels a year and send one letter a month; after serving half their sentence they are permitted to receive one package per year,” – article 65 of the Corrective labor code of the RSFSR of 1970.

Photo: cell for two prisoners. In 1985 it held the Ukrainian poet Vasil Stus and the Russian writer Leonid Borodin

“By sentence of the court, a highly dangerous recidivist may be: a person previously sentenced to prison for highly dangerous state crimes, gangsterism, premeditated murder. (other grave crimes are listed)… and who has committed any of these crimes once again…”

Article 24-1 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR of 1960

In the Mordovian camps, highly dangerous recidivists from the group of highly dangerous state criminals were held in a barracks building separately from the other recidivists, while they all worked together either outdoors or in common workshops, and were locked in cells for the night. The barracks was an old wooden building with stove heating, and the cells did not have toilets – they only had a slop bucket. The prisoners heated the stoves and took out the slop buckets themselves.

In 1980, all highly dangerous state criminals sentenced to special security sections were moved from Mordovia to the Perm-36 political camp, where a special security section was organized, reconstructed from the former sawmill IT No. 6 at the former camp log storage area. It was located 700 meters away from the maximum-security section.

Half of the building was divided into 19 cells, a kitchen and 5 offices, and the second half was divided into two non-cell holding rooms, a bathhouse with a laundry and a linen storage room, a boiler room, an emergency diesel generator, a common toilet for prisoners not held in cells, a small cinema and a storage room for production materials. Two yards for walks were located at the back of the barracks.

The barracks had a system of central heating and all cells had toilets. This was not for the comfort of the prisoners, of course, but for their special isolation. Prisoners were held in cells that were permanently locked – some cells were for habitation, others for work, and prisoners were moved from one to another strictly by one cell at a time, so they did not meet prisoners from other cells.

Prisoners were taken out for walks to the yards by one cell at a time and taken to compulsory film screenings and the bathhouse. The isolation was almost total – for years, the prisoners did not see anyone apart from their fellow cellmates, wardens and “supervisors” – prisoners outside the cells who brought food and production materials to cells and collected finished products – and sometimes the heads of camp administration. The views from the windows of all the cells looked out on to special fences or gates, so that prisoners could not even see the tops of trees growing around the section – only the sky… Nothing apart from the sky and the guards looking down on them were visible from the yard either.

Practically all the political prisoners of these barracks had the same sentence – ten years.