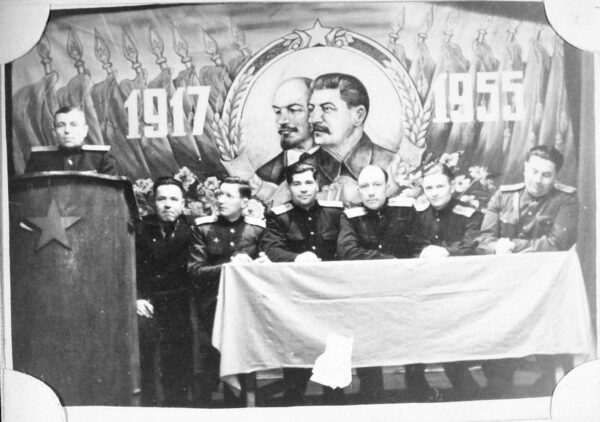

The exhibition is dedicated to Stalin-era political repression in Perm Territory. It was actively displayed by the museum’s mobile exhibition service in all cities and in most villages of Perm Territory. The exhibition included interactive booths with materials on the repression history which were collected in the territories where it was displayed.

Photo of the exhibition

балабанова

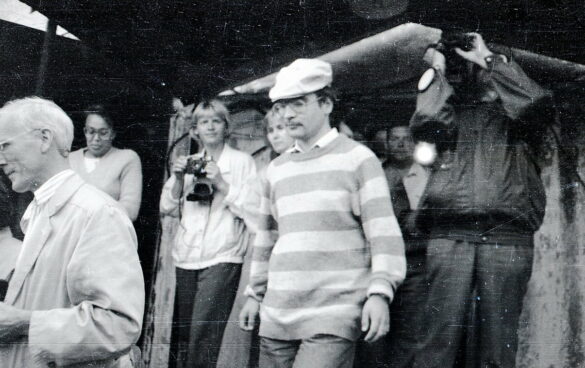

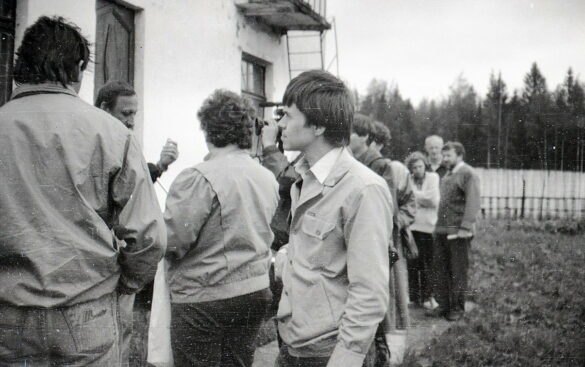

Ural-GULAG Research Center was established in 1992 in order to discover and collect materials on history of political repression and history of Perm political camps. During its two-year existence, the center held two academic workshops in 1993 and 1994 which involved historians of political repression in USSR from various cities of the Russian Federation and Ukraine, former political prisoners from the RF, Ukraine, Lithuania and Estonia, members of the International, St-Petersburg and Perm departments of Memorial, members of the Association of Victims of Political Repression, Russian and foreign guests.

Participants of both workshops visited the former Perm-36 camp, and there discussed prospects and projects of preservation, partial restoration, and museumization of this camp’s buildings and structures. Proceedings of both workshops were published in dedicated collected books.

During the two years, the center’s staff, partners and volunteers:

Compiled a database of available materials on history of political repression in central and Perm public archives.

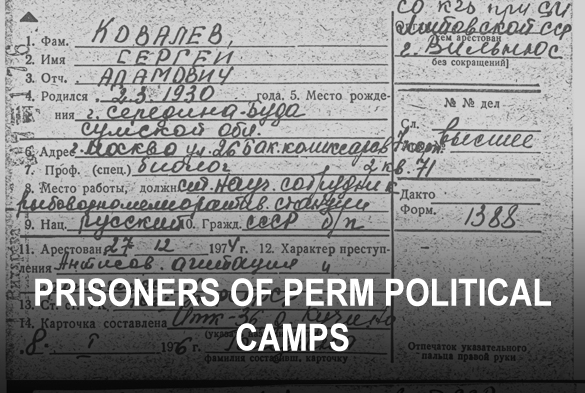

Discovered a package of materials on history of Perm political camps in the archives and the data center (DC) of the MDIA for Perm Region;

Copied the records of some prisoners of Perm political camps at the DC of the DIA.

Interviewed several tens of former prisoners of Perm political camps.

Enquired the out-of-town workshop participants about any materials on history of political repression in former GULAG camps and about road construction involving prisoners which were available to them, as well as about material state of the buildings and structures (most attention was paid to isolated and sparsely populated regions of the country, including Kolyma, Vorkuta, West Kazakhstan, and the routes of the Dead Road).

Made sure that the surviving buildings and structures of the 1940s and early 1950s in Perm-36 camp are the only restorable and exhibitable Stalin-era GULAG-era camp complex.

Developed the first projects for restoration and repair thereof, as well as for using these as the base for the Memorial Museum of History of Political Repression, held the first discussions of this project in Memorial International Society.

In 1994, when Perm-36 Memorial Complex of History of Political Repression and Totalitarianism (Limited Liability Partnership) was established, Ural-GULAG Research Center joined it as its research information division.

The history of the museum “Perm-36” as in a drop of water reflects the history of Russia over the past thirty years.

It began in an era of never-before-seen freedom: archives were opened, thousands of repressed were rehabilitated, monuments were erected to them. The young democratic country looked with horror into its recent past, trying to honestly comprehend and survive this collective trauma.

At this time, since 1992, on the ruins of the former political zone Perm-36, work began on the creation of a museum of the history of political repressions, which was opened in 1995. The museum’s Governing Council included the famous “memorialists” Arseniy Roginsky and Alexander Daniel, President of the Glasnost Defense Foundation Alexei Simonov, Russia’s first Commissioner for Human Rights Sergei Kovalev, and other former dissidents and prisoners of the Perm-36 camp.

But 20 years have passed – and it was a completely different country. The civil society of Russia, which for the first time so solidarily and massively came out in defense of honest elections in 2011, faced a harsh reaction from the authoritarian government. The criminal prosecution of protesters, pressure on human rights organizations, the gradual closure of international projects and initiatives, and finally, the “Law on Foreign Agents”, adopted in 2012 (and in 2022, by the decision of the ECtHR recognized as violating human rights) – all this made the atmosphere in the state everything more suffocating and unfree.

It was during these years that the already world-famous Perm-36 Museum was a platform for the most grandiose civic events – the Pilorama forums, which brought together politicians, human rights activists, journalists, musicians and artists from all over the world. The depth, sharpness and obsceneness of political statements at the Pilorama sites seemed incredible against the backdrop of ever more tightening screws in the country. This short period even brought Perm the glory of the “liberal capital of Russia”.

It all ended abruptly, although it was expected: in 2013, it was not possible to hold the Pilorama forum; In 2014, as a result of intrigues and litigation, the management of the museum complex from ANO Perm-36 passed into state hands, and the founders of the museum – Viktor Shmyrov, Tatyana Kursina and their team – were declared foreign agents. At the disposal of the new administration of the museum were archives, a collection collected over 20 years of work. But its main task was the total re-profiling of the museum and the exclusion from its agenda of any mention of Soviet human rights activists of the 70-80s. Today, the museum exposition does not contain information about the motives and methods of dissidents struggle and about the true reasons for their camp terms in the monstrous conditions of the “Perm triangle” (Perm-35, Perm-36 and Perm-37 zones).

On photo: An art object left in the museum since the Pilorama Forum

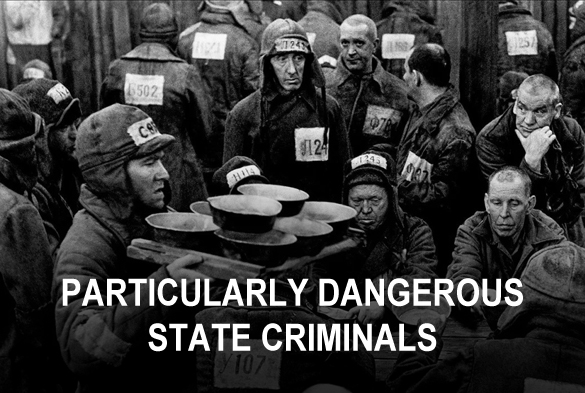

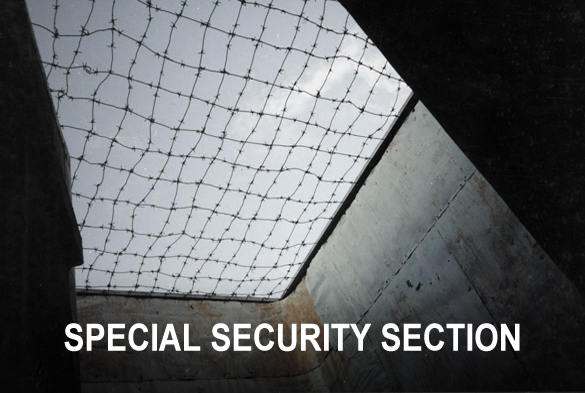

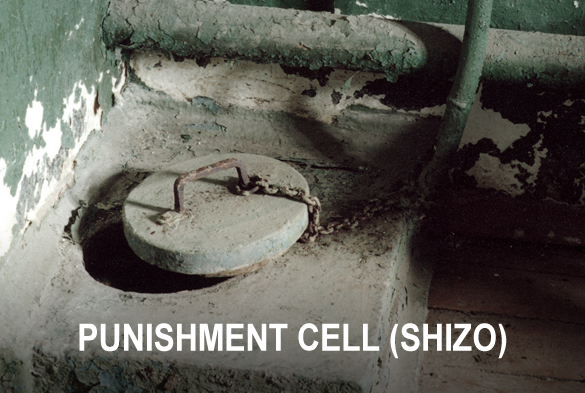

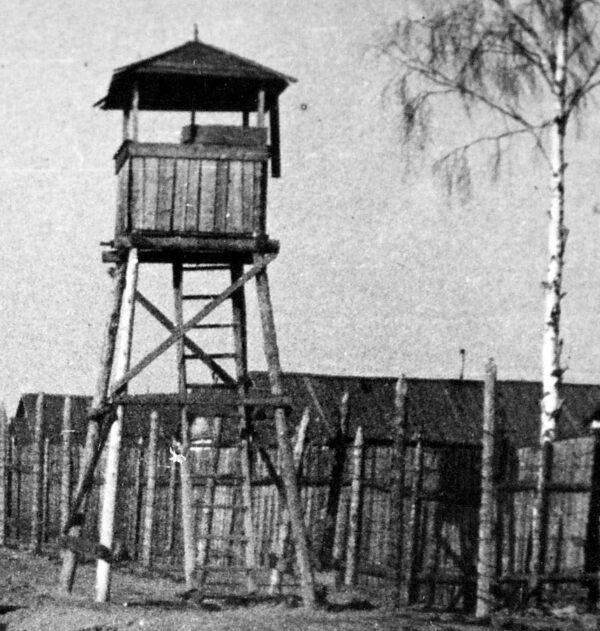

Maximum security was applied to especially dangerous recidivists and exonerated capital convicts. Especially dangerous recidivists could include political prisoners who have already been incarcerated. Unlike other security levels, maximum security provided for 24/7 lockdown.

In 1961 through 1980, ‘supermax’ prisoners of state were kept in the Mordovian maximum-security camp.

The maximum-security area in Perm-36 camp was peculiarly cruel. Most of its prisoners were dissidents who were convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda for the second or even the third time. They were kept in small two/three/four-man cells. Each cell population worked in working cells of the same size, in the same hut. Prisoners from different cells could never meet each other, even when walking from living cells to working ones. They saw nobody but there cellmates and guards for years.

Latticed windows of the cells were blocked from outside by blank blinds, outbuildings or fences. Small iron-clad exercise yards with concrete floors and barbed-wire mesh overhead were used for open-air time. The prisoners could see nothing but the sky outside the windows and the fences for years. Even grass which pierced out through concrete floor cracks was weeded away thoroughly by the guard.

Beside dissidents, this division accommodated exonerated capital convicts who were charged with World-War-II collaboration. They were kept in six-man cells for two-thirds of the term, then switched over to cell-free treatment and engaged in area maintenance.

The Soviet law ‘On Criminal Liability’ 1958 defined ‘especially dangerous political crimes’. The definition included several somewhat reworded ‘counterrevolutionary crimes’ from former criminal codes: high treason, espionage, acts of terror, wrecking, sabotage, anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, war propaganda, attempts to organize especially dangerous political crimes as well as membership in anti-Soviet organizations, and other ‘especially dangerous political crimes committed against any other laborers’ state’.

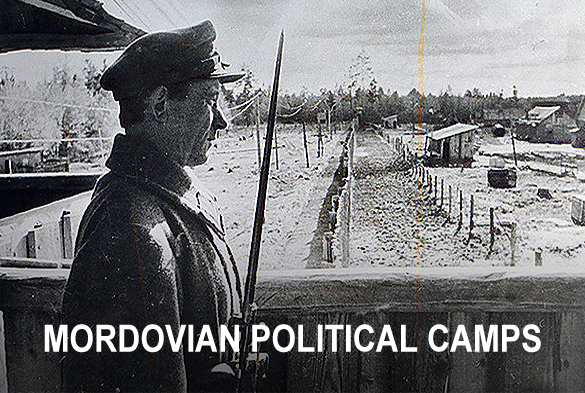

The late 1950s’ legislation provided for ‘supermax’ prisoners of state to be strictly separated from other prisoners. At first such divisions were established in all camps and correctional facilities where such prisoners were kept; in the early 1960s, all of them were collected in Dubravny camp, Mordovian ASSR where nine camp divisions were prepared to that end.

The largest group among them was convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. The second-large group of prisoners consisted of ‘nationalists’ who were convicted of struggle for independence of the territories which were annexed by USSR in the beginning of World War II, mostly West Ukraine and Lithuania. Quite a number of the prisoners were collaborators. Some convicts in these camps were charged with high treason or attempted high treason, with attempts to flee USSR, some with espionage or divulgence of official or military secrets, or with attempts thereof. A few convicts were charged with other crimes which were legally classified among especially dangerous political crimes: terrorism, wrecking, sabotage.

CAMP FOR POLITICAL PRISONERS. 1972 — 1988

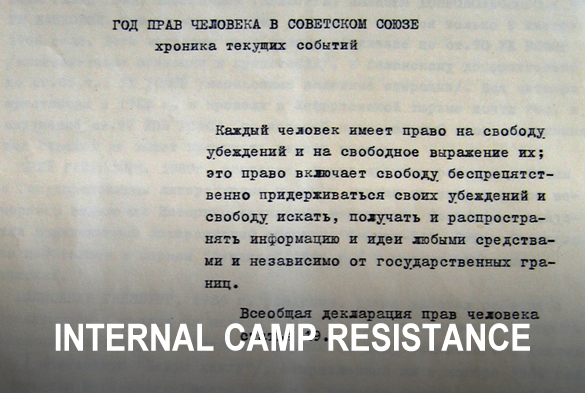

According to USSR, there were no political prisoners in the country while actually there were several categories thereof, first of all, ones convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda who were classified among prisoners of conscience by Amnesty International.

Since early 1960s, all ‘anti-Soviet propagandists’ and ‘traitors’ in the country who were formally classified among ‘supermax’ prisoners of state were kept in dedicated camps, in Mordovian ASSR. Since mid-1960s, convicted dissidents were also sent there but still proceeded with the things they were doing until arrested: recording human rights abuse facts. The information was sent to the outside, spread via underground publications, went abroad, and caused considerable problems to the country’s authorities. The authorities never managed to stop it escaping from the Mordovian political camps, despite all pains and efforts.

It was then decided to establish new, maximum-security camps, and the choice fell, first of all, on the maximum-security correctional facility for convicted enforcement officials, CF УТ-389/6.

On July 13th, 1972, two and a half hundred prisoners were brought there from Mordovia. The camp was recoded from УТ-389/6 to ВС-389/36, while among dissidents, the facility came to be known as Perm-36.

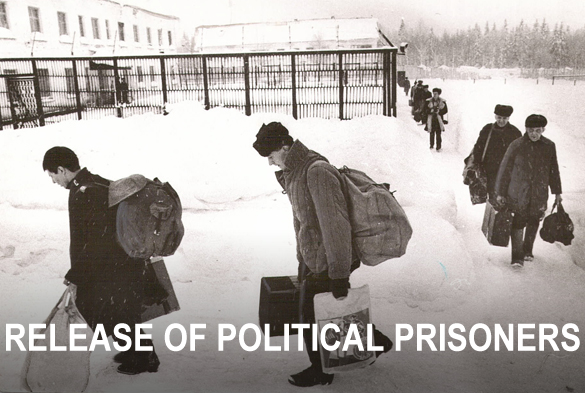

In 1987, when the restructuring began, most prisoners of Perm and Mordovian political camps were granted pardon. Those who were not were concentrated in Perm-35 camp in December of that year. All other political camps, both in Perm and in Mordovia, were either converted to ordinary correctional facilities or totally closed down like Perm-36.

ITK-6 from 1953 to the beginning of the 60s

The Gulag began to shrink the very next day after the official date of Stalin’s death. On March 6, 1953, an order was signed to stop the three largest constructions of the Gulag – a transpolar railway line from the Barents Sea to the Sea of \u200b\u200bOkhotsk and Chukotka, nicknamed the “Dead Road”, a tunnel under the Tatar Strait from Cape Lazarev on the mainland to Cape Pogibi on Sakhalin and the Great Turkestan Canal from the Amu Darya to the Caspian Sea; and on 27 March an amnesty was declared, releasing over a million prisoners. A large number of colonies and camp departments were liquidated in the shortest possible time; liquidated camp zones were abandoned, and where it was not possible to take them out in a short time – along with equipment and materials.

But LO-6 was not abandoned. Already in the autumn of the same 1953, a new contingent appeared in it – convicted law enforcement officers: former employees of the Ministry of State Security, the prosecutor’s office, the police and the camp administration, accused of falsifying cases and other professional abuses. On July 1, 1954, there were already 469 of them. We do not know the personal composition of the prisoners of that period, its archives are completely inaccessible, but according to individual remarks in the protocols of party meetings that mentioned colonels and generals among the prisoners, as well as special procedures in the colony at that time, we can assume that these were mainly middle-level leaders camps, courts, prosecutors and police, which fell under the purge after the arrest and execution of Beria. The camp was popularly called “Cop Zone”.

These were the special rules. When in 1961 a television center began to function in Perm, one of the first televisions in the area appeared in the camp club, for which an unusually high mast with an antenna was installed that received a signal from Perm at a distance of 80 km. In the same year, prisoners were shown 18 films in two months, including 9 foreign films, while ordinary prisoners were allowed 2-3 films a month. Some prisoners were granted personal visits more frequently than was instructed. Prisoners were allowed to visit the village club outside the camp, and on weekends they were given leave as a reward.

In 1956, the prisoners refused dinner, because instead of the traditional pink salmon, cod was prepared for them. After the camp uprisings and mutinies of 1953-1954, which usually began with such private conflicts, such collective protests by prisoners were immediately reported to Moscow. Cod was removed from the ration and the employee who allowed it was punished.

Hard work at the logging site was replaced by timber processing, for which a large workshop with a set of woodworking machines and a sawmill was built half a kilometer from the camp, on the territory of a former rafting ground. However, refusals to work and cases of disobedience were almost a common practice. The camp commanders had the rank of senior lieutenant or captain, and among the prisoners were not only former colonels, but even generals. The internal discipline of this period is most clearly characterized by the officially recorded fact that the prisoners beat the head of the camp.

On December 8, 1958, the Regulations on Correctional Labor Colonies and Prisons were adopted, according to which all camps began to be called colonies. Moreover, the very word “camp” began to become obsolete, it was officially banned from use in the press. LO No. 6 again became ITK-6. But this replacement did not take root among the people, and in everyday life the camps were still called camps.

ITK UT-389/6 from the early 1960s to 1972

In the early 60s. in all the republics of the USSR, new criminal codes came into force, and amendments were made to the existing corrective labor codes and internal regulations, which unified the activities of all correctional labor institutions in the country. By this time, almost all the prisoners, the former big bosses, left ITK-6 in one way or another, and its contingent was gradually renewed again. Most of it was made up of privates or ranks of the junior and middle commanding staff of law enforcement agencies, convicted of ordinary criminal offenses: theft, bribery, bodily harm, murder. There were many police drivers among them – the perpetrators of traffic accidents with victims, etc.

ITK-6 became known as ITK UT-389/6, where the cipher UT-389 denoted the Perm Department of Correctional Labor Institutions (UITU). The camp buildings practically did not change, only the old barracks were periodically repaired, and a department for bedridden patients with ten beds was attached to the first-aid post. This whole building, which was called from that time the medical unit, was sheathed with a herringbone tare board, the repaired watch in the transition between the living and working areas, which was called from that time the “room for searches”, was sheathed with the same “herringbone”. There were flower beds in the camp.

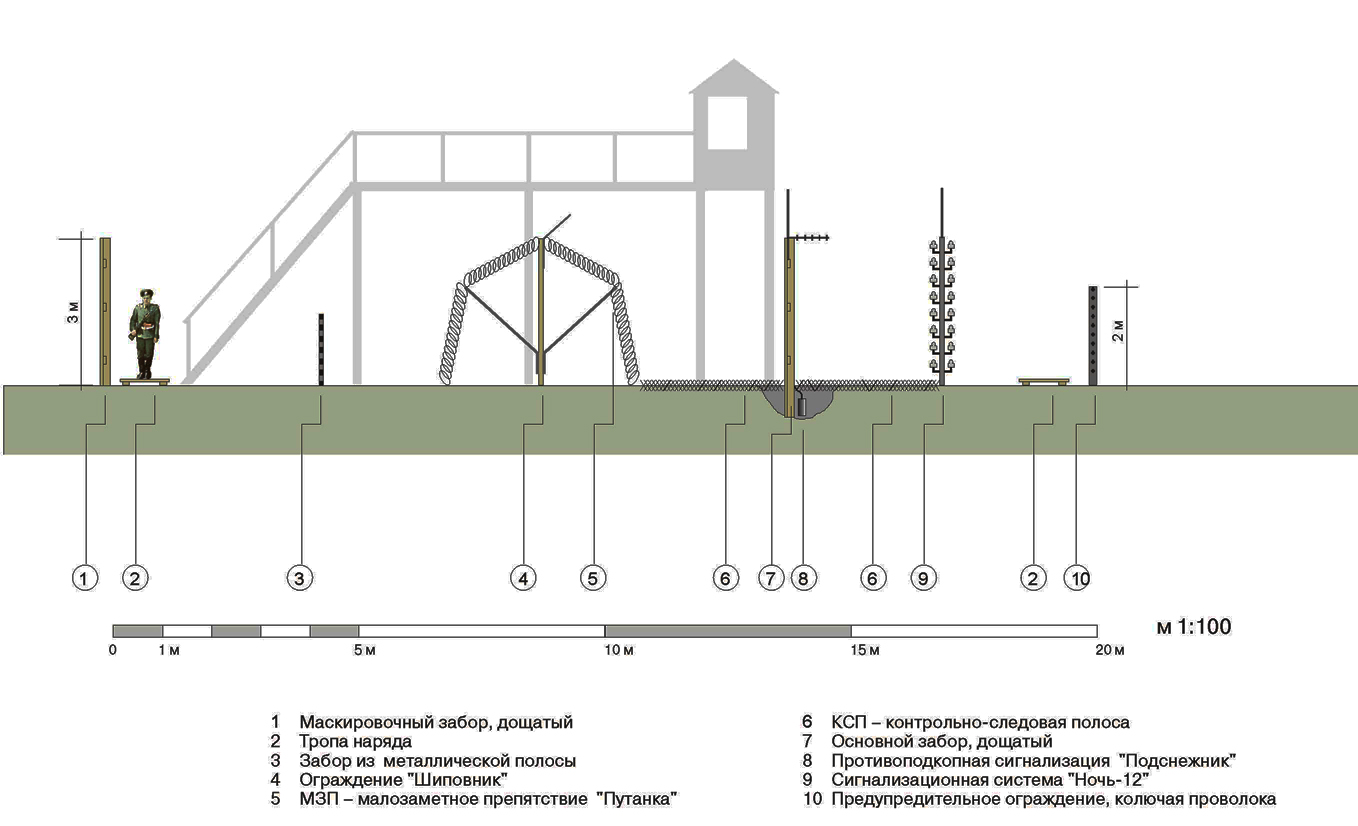

At the same time, much attention was paid to the system of security fences – among the prisoners there were many young, trained men who, in addition, knew well the construction of conventional fencing systems, the orders and rules of security, and therefore were especially dangerous in the event of an escape. Therefore, these systems were constantly improved: plowed control and trail strips, wide restricted areas, shot from towers, and signaling systems appeared.

For the same security reasons, there was no logging site in the camp: the camp could not provide sufficient and reliable convoy for the forest plots. Logging was carried out by prisoners from two forest areas, probably ordinary criminal prisoners. And although another production zone with a timber workshop and a sawmill was organized away from the camp, there was not enough work for all the prisoners and this was a big problem for the camp administration.

At the beginning of the summer of 1972, an unexpected order was received – to transfer the entire special contingent to the colonies for convicted law enforcement officers of Nizhny Tagil and the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and to prepare ITK-6 to receive a new contingent.

In ITK-6, one of the four barracks built in 1946 was demolished and a brick headquarters building with a camp club was built in its place, and next to it was a common brick unheated toilet (previous prisoners used the toilets in the barracks). In addition, concrete paths were recast and camp fences reinforced. In July, the camp was ready to receive a new contingent…

In 1946, the correctional facility was relocated near Kuchino. 4 250-man huts were erected by the prisoners at the new site. The huts were built of raw, as-felled wood, and began rotting quickly. As early as in 1949 the camp authorities reported these to be worn by more than 40%.

In 1948, a political department board of Molotov Administration of Correctional Camps and Facilities reported after examining the camp: ‘… the prisoners are found in mattresses and blankets by 30%, bedclothes and pillows totally unavailable… All windows require glazing but glass is unavailable’. In 1948, only about 1.5% of the prisoners were ‘completely able-bodied’, 48% ‘partially able-bodied’, the rest ‘mostly incapacitated’, that is to say, they were either disabled or ‘wasted’: emaciated by starvation, backbreaking work, and diseases.

As early as by 1948, the near-camp forest was completely devastated, it took more than two hours to convoy the prisoners to the allotments one way. Such camp sites were generally abandoned and new one erected deeper in the forest but this one had to be left in place because there was no other convenient nearby site to store logs which were harvested over year. The rotting huts were therefore repaired, trucks and tractors provided to transport prisoners and haul logs. Workshops were built around the camp. In 1952, the penitentiary was reclassified from a correctional facility to a camp division.

GULAG. 1942 - 1953

The GULAG as a phenomenon of monstrous exploitation of a huge number of prisoners, mostly innocently convicted – existed for only a quarter of a century: from 1929 to 1953. And as an institution – the Main Directorate of the Camps of the NKVD-MVD of the USSR – from 1934 to 1959. But for many decades, if not centuries, the Gulag left the whole of humanity with a traumatic memory of a pitch hell on earth. These traumas – traumas of lawlessness of power and obedience of the population – relapsed in the current insane war…

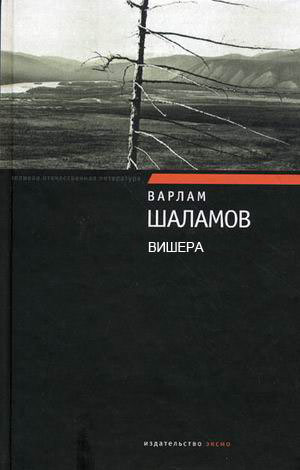

The GULAG was born in the same place where the political camp of the USSR ended its history much later – in the Perm Territory. In 1929 – 1934, the Vishera Pulp and Paper and Berezniki Chemical Plants and a dozen smaller enterprises were built here with the help of tens of thousands of prisoners, not counting the numerous forest “business trips”. Both plants were built for the needs of the army: cellulose was used to produce gunpowder, and nitrogen was used to produce explosives.

The work was supervised by the rear service of the Red Army (Workers ‘and Peasants’ Red Army), and the prisoners were supplied to the construction sites by the political police – the GPU (State Political Administration). This was the first experience of the mass use of prison labor. The experience came to the court, and the organizer of the construction, the Red Army divintendant and an employee of the special department of the Cheka-OGPU of the USSR E. Berzin in 1932 was sent to disseminate this experience in Kolyma, where he created the most terrible, as they were called, “extermination-labor” camps.

One of the “builders” of the Vishera and Berezniki combines was Varlam Shalamov – a great writer in the future, and then a prisoner of VISHERON, the Vishera special purpose camp, who left his testimony about it – the anti-novel Vishera.

“The camp zone, brand new, brand new, shone. Each barbed wire in the sun shone, shone, blinded the eyes. Forty barracks – the Solovetsky standard of the twenties, two hundred and fifty seats in each on solid bunks on two floors… The columns of the camp club were somewhat reminiscent of the Parthenon, but were worse than the Parthenon “

V. Shalamov” Vishera “

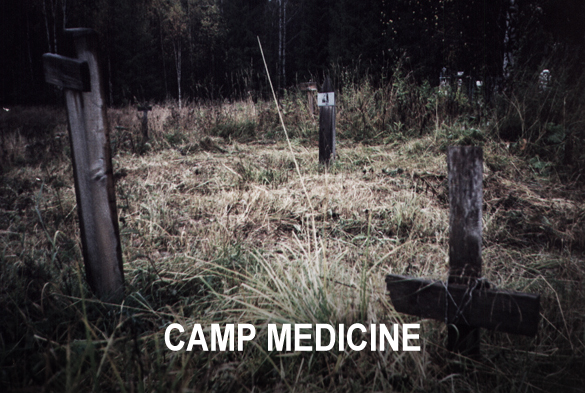

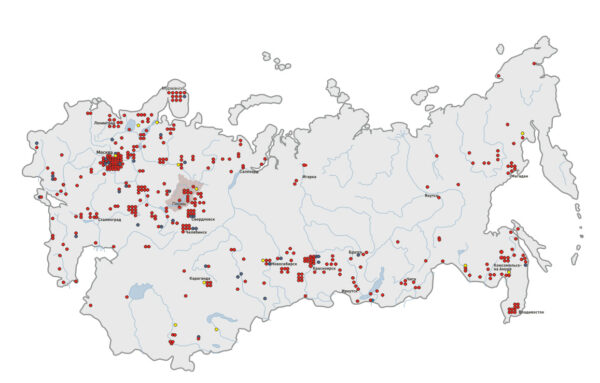

During the existence of the Gulag, 474 corrective labor camps (ITL) were established in it. At that time, not every separate “zone” was called a camp, as it will be confirmed in everyday consciousness later, but an institution that includes from one to several dozen such “zones”: camp departments (LO), camp points (LP), colonies, “business trips ”, “posts”. In these “zones” there were from several tens to many thousands of prisoners. So in the North-Eastern ITL (SVITL, Kolyma) on July 1, 1940, according to its accounting and distribution department, there were 190,309 prisoners. In addition, in each region and territory, there were territorial directorates of corrective labor camps and colonies (UITLK) with their own camps and colonies. In 1952, the total one-time number of prisoners of the Gulag and territorial UITLK exceeded two and a half million people. And for a quarter of a century, several tens of millions passed through the camps. And no one knows yet how many of them are left in the camp cemeteries.

Correctional labor colony No. 6 (ITK-6) of the Molotov UITLC was the smallest fragment of this entire empire of slavery in the 20th century, but a fragment in which the entire “archipelago” was reflected.

ITK-6 Molotov UITLK in 1942-1946

ITK-6 of the Molotov UITLK (Office of Correctional Labor Camps and Colonies) was created at the most difficult time for the country – in the late autumn of 1942. Its creation was caused, apparently, not by production needs, but by the need to employ an ever-increasing number of prisoners. The colony was logging. And the organization of logging camps was a reliable way to “utilize” the newly convicted.

When a wave of the Great Terror swept over the country in 1937-38 and over 700 thousand people were thrown into the Gulag within a few months, two Gulag orders dated August 16, 1937 and February 5, 1938 created thirteen large forest camps in the space from Onega to Taishet, containing half of this amount. And the forest is always needed, and it was easier to organize these camps: the prisoners would not only cut down the forest and take it out along the roads laid by them, but they would also build the camps themselves.

But the prisoners of ITK-6 did not succeed in building stationary barracks until 1946: although their number in 1944 amounted to over 800 people, they were scattered across forest plots in the surrounding forests along the Chusovaya River over a space of more than fifty kilometers. The location of the logging sites and the headquarters of the colony changed many times during this period – the colony was consistently far from fulfilling the planned targets, its leadership explained this either by the scarcity of the allocated timber fund, or by inconvenience or the hauling distance (mechanical delivery) of the harvested timber, and this caused constant displacement of the colony units.

The contingent of the colony was diverse: there were both men and women, and teenagers – boys and girls, starting from 15 years old. Most of them were sentenced to short terms for petty theft, for hooliganism, for unauthorized leaving the work of defense industry enterprises and vocational schools, for home brewing and petty speculation. But there were also those convicted on charges of counter-revolutionary crimes and “for five ears of corn”, as the people said – according to the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of August 7, 1932 “On criminal liability for theft of state or collective farm-cooperative property.”

Labor in the colony was extremely hard: the prisoners not only sawed the forest, but also manually pulled the logs from the plots. There were few horses of their own in the colony, and from starvation they were also weak. And the authorities ordered the local residents to allocate collective farm horses for the colony, which was a heavy dues for the collective farms, and they either evaded it as best they could, or supplied horses that were completely weak. The life of the prisoners was more than meager: many of them could not meet the prescribed production rate and received a “guarantee” – a minimum daily ration of 600 grams of black, usually poorly baked bread, because for reasons of economy, bread in the colonies preferred not to buy, but the stove ourselves, and a bowl of camp balanda – a very thin, tasteless and nutrient-poor stew.

In 2012, the new authorities of Perm Region, headed by the Governor newly appointed by Moscow, denied funding for repairs of the former camp’s buildings and constructions. During more than two years Perm-36 Memorial Center proceeded with certain crucial restorations and conservations from extrabudgetary funds, raised independently, but these activities were also discontinued in 2014, after the museum was taken over by the state.

The previous repairings allow to preserve the Memorial Center for some years, unless any contingencies occur. However, discontinuation of systematic monitoring at least of three objects, i.e. the former camp’s bath/laundry, the smithy and the manufactories, initially started by Perm-36 Memorial Center but stopped when the museum was taken over, is of serious concern. The intention of new regional authorities to defund the repairings of the Memorial will unevitably result in irreparable losses.

Most of the worry is that these incompletely repaired objects are in danger of fast degradation. The camp fences are also decaying.