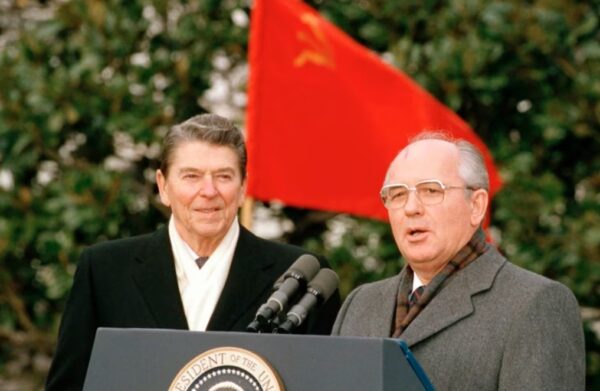

In October 1985, Ronald Reagan met for the first time with Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva, where they discussed the need to curtail the arms race and limit strategic and nuclear weapons. At the end of the meeting, Reagan mentioned human rights and political prisoners in the USSR – like his predecessor Jimmy Carter, he had made these issues part of his election campaign. Gorbachev exploded: “I’m not your pupil, Mr. President, and you’re not my teacher!”

In February 1986, Gorbachev announced in an interview with L’Humanité: “…concerning political prisoners. We do not have them in our country… we do not persecute citizens for their convictions.” But at the meeting between the leaders of the USA and the USSR held in Reykjavik on 11-12 October of the same year, the issue of political prisoners and human rights was officially placed on the agenda. In subsequent months, departments of human rights were formed under the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

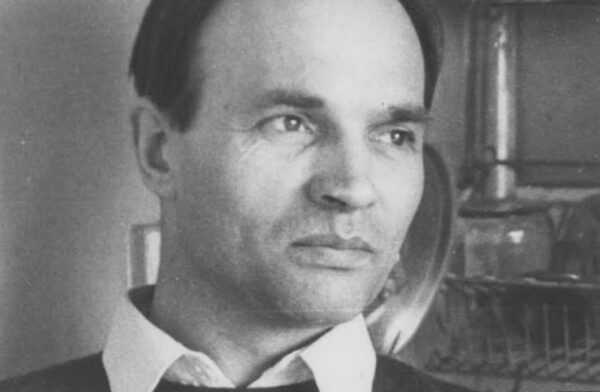

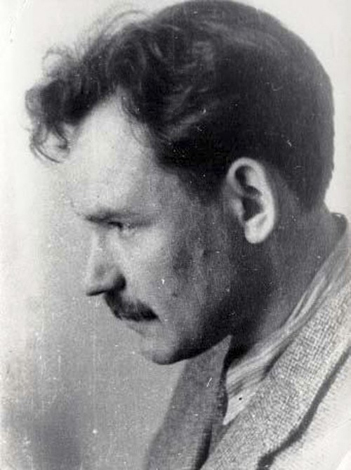

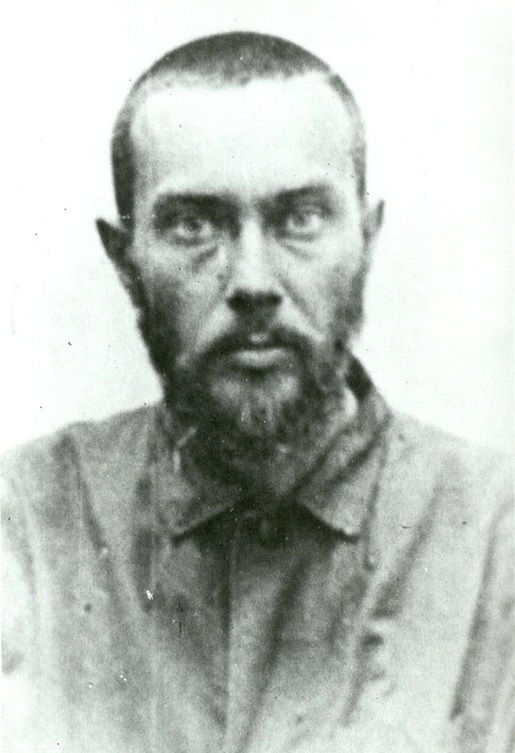

On 28 November 1986, Anatoly Marchenko, who was serving his sixth prison sentence, stopped a hunger strike after 117 days, which he had begun with the demand to release all political prisoners. He had previously spoken with a representative of the Communist Party, who had flown specially to the Chistopol prison. But the hunger strike had seriously damaged Marchenko’s health, and on 8 December he died. On 16 December, Gorbachev called Andrei Sakharov to inform him that he had been released from his exile in Gorky.

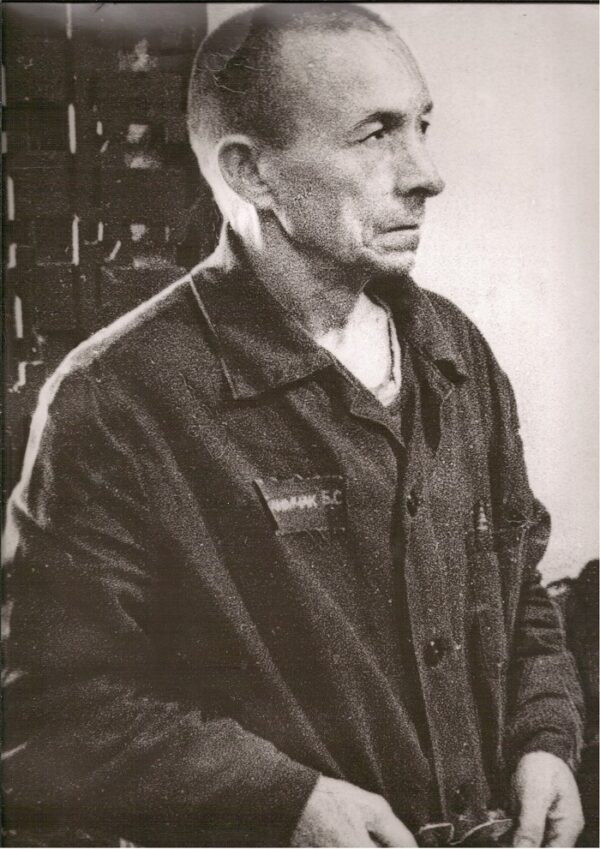

In early February 1987, the release of political prisoners began, and continued for 20 months. All prisoners whose main charge was anti-Soviet agitation was released from the Perm and Mordovian political camps, and also from exile. Initially, their release was dependent on amnesty, requiring a personal, written petition by the prisoner. This meant confessing to the crimes, and recognizing the lawfulness of the trial and the justice of the sentence. Far from all political prisoners were prepared to make this confession. Those who refused were then told: “If you don’t want to request forgiveness, at least write something”. But eventually they were all released without even this requirement.

The last political prisoner sentenced for anti-Soviet agitation, Bogdan Klimchak, was only released on 11 November 1990. The main charge in his sentence was treason – he had tried to flee the country. He was also carrying several dozen pages of “anti-Soviet and slanderous documents”, mainly of his own composition. The schedule and procedure for releasing the political prisoners were undoubtedly controlled by the KGB.

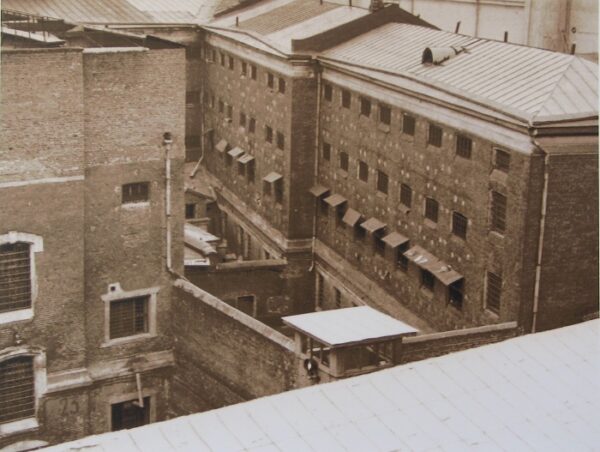

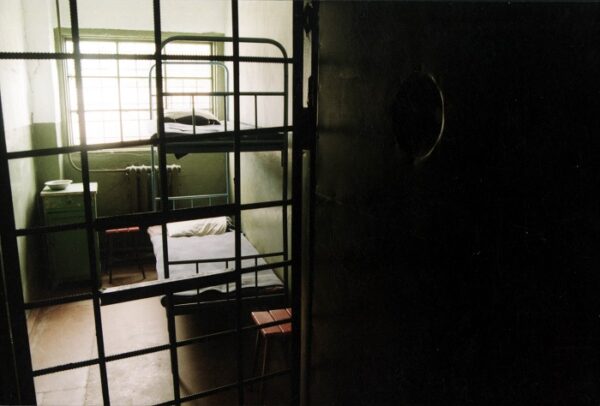

The mass release of political prisoners meant that all the political prisons of Mordovia, and also the Perm-36 and Perm-37 camps, were almost empty by the end of 1987. The prisoners remaining, mainly sentenced on charges for treason – collaboration, attempting to flee the USSR, espionage and revealing state or military secrets – and also anti-Soviet prisoners who the KGB were for some reason reluctant to release, were gathered together in the Perm-35 camp. The last “traitors” were released from this camp on 7 February 1992.

After the release of the highly dangerous state criminals, the Mordovian political camps and the Perm-37 camps were reformed in 1988 into conventional criminal corrective labor camps, and the Perm-36 camp was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Perm Oblast department of social welfare to house a neuropsychiatric care home.