An entire era has come to an end. We mourn. There are no words🖤

Personal file

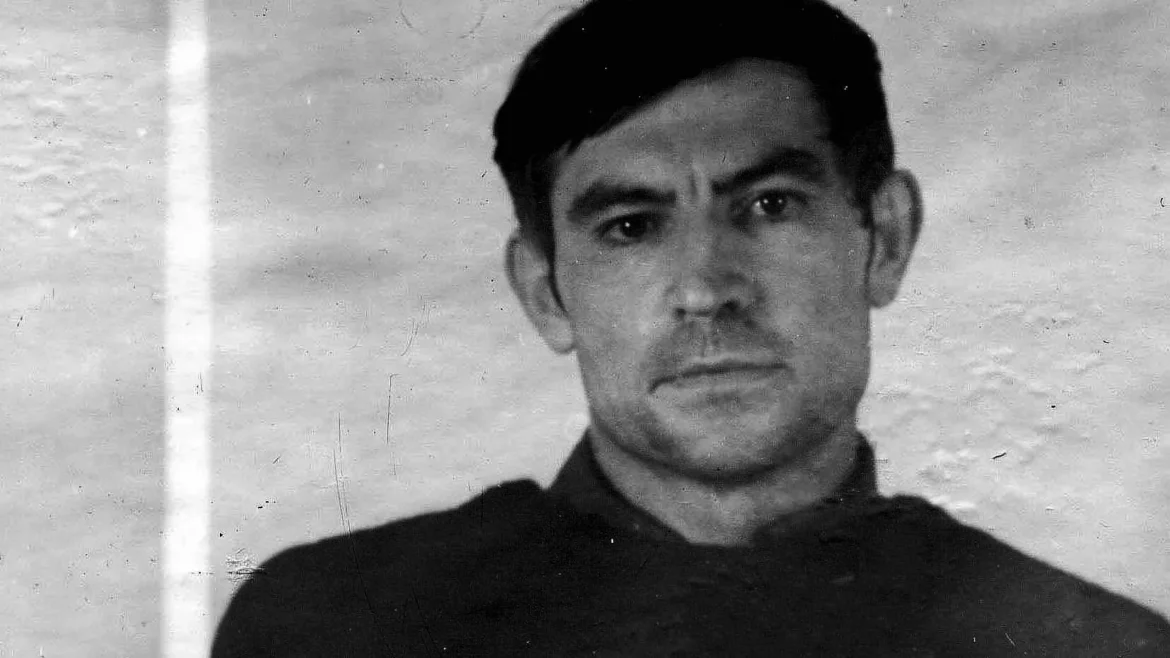

Perm Opposition Politician Konstantin Okunev Spends His Birthday Behind Bars on Politically Motivated Charges

On 5 December 2025, Perm opposition politician and former member of the Legislative Assembly of Perm Krai Konstantin Okunev spent his 57th birthday in a pre-trial detention center. His arrest on charges of “justifying terrorism” raises serious concerns about its legitimacy and is widely viewed by human rights defenders as politically motivated.

Okunev was detained on 29 October and placed in Perm’s Detention Center No. 1 (SIZO-1) by a ruling of the Leninsky District Court, which ordered that he remain in custody until 28 December. The case was opened under Article 205.2(2) of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation — according to investigators, the grounds for prosecution were statements published on his Telegram channel.

Konstantin Okunev has long been one of the most prominent figures in Perm’s opposition. He served in the Perm City Duma and the regional Legislative Assembly, openly criticized federal and regional authorities, condemned political repression and restrictions on civil liberties, and consistently supported civic initiatives and independent activists. For his position, he faced pressure many times, including fines, administrative cases, and public attacks. The current criminal prosecution is the most severe pressure campaign against him to date.

Shortly before his birthday, the Federal Financial Monitoring Service (Rosfinmonitoring) added Okunev to its registry of “terrorists and extremists,” further worsening his situation and imposing additional restrictions — including the blocking of financial transactions — even before a court verdict.

The team of the virtual museum “Perm-36” expresses solidarity and support for Konstantin Okunev. For a person held in isolation, words of support are especially meaningful, especially on such days. We encourage everyone to send him a letter or a postcard.

Address for letters: 614000, Perm, Klimenko St. 24, Detention Center No. 1 (SIZO-1),

Konstantin Nikolaevich Okunev, born 05.12.1968.

Write to political prisoners — it truly matters to them, and it is safe for those who write.

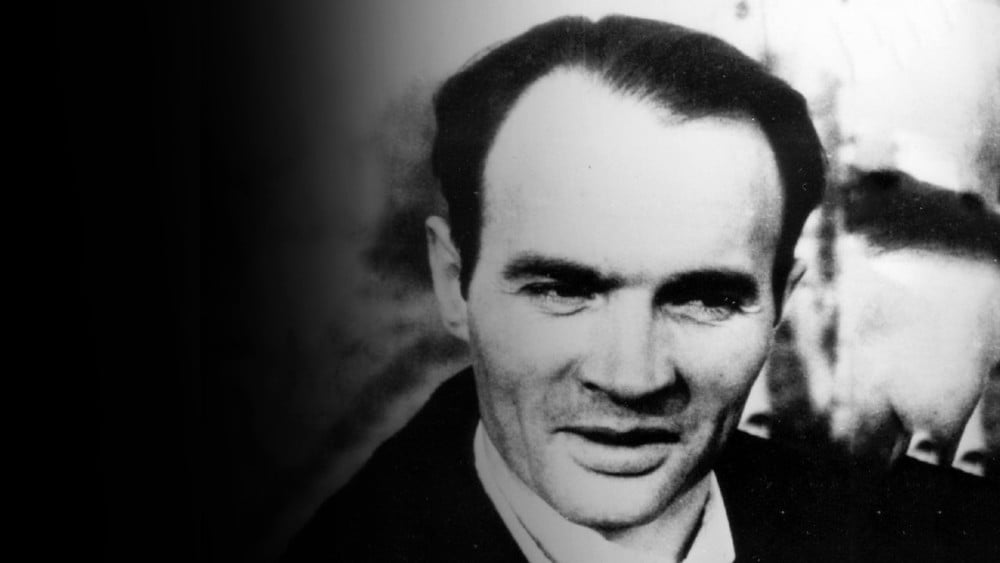

Russian Human Rights Defender and Dissident Valery Borshchev Dies in Moscow

On November 3 Valery Borshchev — a human rights defender, public figure, Soviet dissident, and journalist, as well as the author of the law on public oversight of places of detention — passed away at the age of 82.

Valery Borshchev was born on December 1, 1943, in the village of Chernyanoye, Tambov Region. He graduated from the Faculty of Journalism at Moscow State University. After meeting Andrei Sakharov in 1975, he became actively involved in human rights work, for which he was banned from practicing journalism. Thanks to the support of Valery Zolotukhin and Vladimir Vysotsky, Borshchev found work at the Taganka Theatre, where he served as a carpenter, painter, and firefighter.

In 1982, he was severely beaten because of his human rights activities, and in 1985, the KGB classified his work as “anti-Soviet propaganda.”

From December 1994, Borshchev was part of Sergei Kovalev’s group, which operated directly in the conflict zone in Chechnya. During the First Chechen War, he helped evacuate women and children from combat areas, according to the Moscow Helsinki Group.

In June 1995, during the Budyonnovsk hostage crisis, he volunteered to take the place of a hostage.

Borshchev co-authored the law on public monitoring of detention facilities, which later led to the creation of Moscow’s Public Monitoring Commission — an institution he went on to lead.

He was a member of the Moscow Helsinki Group and became its co-chair in January 2019.

In recent years, Valery Vasilyevich suffered from serious illness.

May his memory live on.

Read more about Valery Borshchev in Radio Svoboda’s article “A True Hero.”

Street Singer Detained in Perm for Solidarity Concert Supporting Arrested Musicians

In Perm, a young street performer, Yekaterina Romanova, was detained for organizing a solidarity concert in support of the members of the St. Petersburg band “Stoptime.” According to the Telegram channel Perm 36.6, a local pro-war activist filed a complaint against her, claiming that the concert, held on October 22, made him miss his bus.

Following her detention, police charged Romanova under Article 20.2.2 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offenses — for “organizing a mass gathering of citizens in a public place that disrupted public order.” Her court hearing was scheduled for November 1, but defense lawyer Aleksei Ogloblin requested to be summoned to court, and the session was postponed.

Yekaterina Romanova

The Stoptime group gained recognition for performing songs by musicians labeled “foreign agents” in Russia. Since mid-October, its members — vocalist Diana Loginova (Naoko), guitarist Alexander Orlov, and drummer Vladislav Leontyev — have faced administrative cases for “unauthorized protests” and “discrediting the army.” They have been fined and repeatedly placed under administrative arrest.

After the arrests, street musicians across Russia began performing songs in Stoptime’s support, while bloggers and artists published solidarity videos online.

Photo: Perm 36.6

Remembering Anatoly Marchenko: Scholars Gather in Milan to Revisit a Dissident’s Legacy

From November 3 to 5, 2025, an international conference titled “Readings in Memory of Anatoly Marchenko” will take place in Milan. The event will bring together historians, human-rights researchers, and literary scholars to examine the life and legacy of Anatoly Marchenko — one of the most prominent Soviet dissidents, who died in prison in 1986 after a prolonged hunger strike.

Marchenko’s uncompromising stand against political repression and his writings about Soviet labor camps made him a symbol of moral resistance. His 1968 open letter on the plight of political prisoners declared:

Our civic duty, the duty of our human conscience — is to stop crimes against humanity. The crime begins not with the smoking chimneys of crematoria, nor with ships bound for Magadan — it begins with civic indifference.

Posthumously, in 1988, Marchenko received the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought from the European Parliament. A year later, his works — My Testimony, From Tarusa to Chuna, and Live Like Everyone — were officially published in the USSR for the first time.

Despite his historical significance, Marchenko’s civic and literary heritage remains under-studied. The upcoming Milan conference aims to change that.

Key themes will include:

- Marchenko’s biography and archival research;

- His texts as documentary testimony and part of Russian literature;

- Translations and Western reception of his works;

- Marchenko and the Soviet dissident movement;

- The relevance of Marchenko’s moral witness to contemporary human-rights debates.

Working languages: Russian, English, Italian.

For inquiries: [email protected]

Programme and registration details:

🔗 Anatoly Marchenko International Conference — Milan (3–5 Nov 2025)

Let the swans dance! Young street singer arrested for performing banned song

In St. Petersburg, an 18-year-old music college student, Diana Loginova (stage name “Naoko”), has been detained and sentenced to 13 days of administrative arrest after performing the song “Swan Lake Cooperative” by Noize MC — a track recently banned in Russia as “extremist”.

Loginova performed on a busy street with her band Stoptime, drawing a crowd that police say blocked access to a metro station — leading to charges of organising an unsanctioned public event. The crowd videos, shared online, featured the young singer and audience chanting lyrics including:

I want to watch the ballet, let the swans dance. Let the old man shake in fear for his lake.

The song references the dacha cooperative Ozero, known to be linked with President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, and the ballet Swan Lake—which has historically been used on Soviet and Russian TV to signal regime change. Russian courts banned the track in May 2025, saying it contained “propaganda for violent change of the constitutional order”.

Two musicians from Stoptime also received administrative penalties. After serving her term, Loginova is expected to face additional administrative charges under Russia’s “discrediting the armed forces” law, which could lead to criminal liability if she re-offends.

Human rights experts say the case may mark a broader trend of cultural repression — where even street performances and youth music are subject to state control. The arrest underscores how public art is increasingly treated as a form of dissent in Russia’s current climate.

The virtual museum “Perm-36” expressed solidarity with Diana Loginova and other persecuted musicians, emphasizing that freedom of artistic expression must not become a punishable act. We believe that art and honesty should never be crimes. And yes — let the swans dance again.

Source: Reuters — Russian street musician is jailed for 13 days after she played banned song.

Beaten in Perm Krai — Ukrainian Journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna Dies in Russian Detention

Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna died in Russian custody on September 19, 2024, at Pre-Trial Detention Center No. 3 in the city of Kizel, Perm Krai. Initially held in a detention center in Taganrog, Rostov Oblast, she was transferred to Kizel eight days before her death, according to an investigation by Slidstvo.Info (source).

Her death certificate, issued by the Leninsky Department of the Civil Registry Office in Perm, confirms she died in Kizel. The Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine also verified these facts.

According to a released Ukrainian serviceman, Roshchyna appeared emaciated but could walk unaided. He reported that detainees in Kizel endured brutal beatings and psychological pressure. Women prisoners, he said, were shaved bald. These claims were confirmed by Mediazona, which reported that several Ukrainian prisoners were transferred to Kizel from Taganrog in the fall of 2024 (source).

After her death, Roshchyna’s body was returned to Ukraine without certain internal organs, raising serious concerns about torture and human rights violations in Russian detention facilities.

Perm Krai, historically known as a place of mass repression and exile — sometimes called “the prison of nations” — has again become a site of tragedy, continuing its grim legacy.

Viktoriia Roshchyna, 27, was taken prisoner in August 2023 in Enerhodar during the Russian occupation of the Zaporizhzhia region. She worked as a freelance reporter for Ukrainska Pravda. Held in various detention facilities in both occupied Ukraine and Russia, she reportedly suffered severe torture and extreme weight loss, down to 30 kilograms, before her death (source).

Human rights organizations and the international community call for a full, independent investigation into her death and demand accountability for those responsible.

Related Links:

On September 18, Lviv hosted the presentation of two new books by poet, musician, human rights defender, and former political prisoner Mykola Horbal — On the Roads of the Patriarch and In Search of Christ. For many years of his life, the author endured Soviet labor camps, including the notorious Perm-36, where numerous Ukrainian and Moscow dissidents were imprisoned. The event was moderated by Horbal’s long-time colleague and fellow former Perm-36 inmate, Myroslav Marynovych.

Mykola Horbal was born on September 10, 1940, in the village of Volovets in Lemkivshchyna. Trained as a musician and teacher, he began writing poetry in his youth and developed a deep interest in Ukrainian history and culture.

In 1970, Horbal was first arrested on charges of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” He was later tried again on similar accusations and ultimately spent more than sixteen years in prison and exile. Despite the harsh repression, he became an active member of the Ukrainian human rights movement, joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, and contributed to the samizdat publication The Chronicle of Current Events.

His years in Perm-36 in the late 1970s were especially difficult. There, he was imprisoned alongside prominent dissidents such as Viktor Marchenko and Myroslav Marynovych. Horbal was accused of distributing “slanderous materials” and of supporting the Helsinki Group. Subjected to constant pressure and punishments for “disobedience,” he nevertheless emerged as a steadfast defender of human rights and a poet who preserved his inner freedom.

Many leading dissidents — including Vasyl Stus, Viktor Marchenko, Semyon Kirichenko, Gleb Supperfin, Sergei Kovalev, and Elena Bonner — spoke out in his defense. Horbal remained loyal to his beliefs even under strict-regime conditions, and after his release he continued his literary and civic work.

Today, Mykola Horbal’s writings and life story stand as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and to the memory of resistance against oppression that unites the fates of those imprisoned in the camps of Russia’s Perm region.

Yulia Navalnaya: Independent Laboratories Confirm Alexei Navalny Was Poisoned in Prison

The widow of the Russian opposition leader has released a video message stating that foreign independent laboratory tests have confirmed: on 16 February 2024, Alexei Navalny was poisoned while in a Russian prison.

Yulia Navalnaya said:

In February 2024 we managed to secure, transfer abroad, and submit for analysis biological samples of Alexei… Laboratories in two different countries, independently of each other, came to the conclusion that Alexei was poisoned.

She emphasized that the reports from the laboratories have been ready for several months but have not yet been published for political reasons, and she has called for their disclosure:

I demand that the results of the analysis of what exactly poisoned my husband, Alexei Navalny, be revealed. I demand this for myself, for our children, for Alexei’s parents, for our supporters in Russia, and for all people around the world who fight for freedom and justice.

Let us recall that in 2020 Alexei Navalny was poisoned with a nerve agent of the Novichok group and survived. Despite international investigations, Russian authorities have denied involvement in both incidents.

Reliable English-Language Source:

“How good it is that I do not fear death.” 40 years since the death of Vasyl Stus

On September 4, 1985, Ukrainian poet and human rights defender Vasyl Stus died in the Soviet labor camp Perm-36. He was 47 years old. His death became a symbol of the ruthless pressure exerted on political prisoners in the USSR — and at the same time, a testament to the unbreakable will and enduring power of the written word.

A life dedicated to truth and justice

Vasyl Stus was born on January 6, 1938, in the village of Rakhnivka, Cherkasy region. He became known as a poet, translator, and civic activist who consistently opposed political repression and human rights violations.

In 1972, he was arrested for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” and sentenced to five years in prison. After his release in 1979, Stus resumed his human rights work and was arrested again in 1980. This time, the sentence was harsher: 10 years in a strict-regime labor camp followed by 5 years of internal exile.

Perm-36 was one of the toughest Soviet prison camps for political dissidents, where writers, activists, and human rights defenders were held in brutal conditions. Even there, Stus continued to write, capturing in verse both his inner struggle and the broader tragedy of his generation.

Words that defied silence

One of Stus’s poems reflects the loneliness and quiet defiance that defined his life behind bars:

O my God! What sorrow I endure,

and boundless is my solitude.

My homeland — gone. My cautious eye

gropes the road between the voids.

This is my path — return, or not.

This is my path — the world’s edge, my only guide.Forgive me, wife. Forgive me, son.

Mother — do not curse my fate.

I go away. Shalom. At random,I go away, weary of rage…

Vasyl Stus died in the punishment cell of Perm-36 under unclear circumstances. In one of his last messages to his son, he wrote lines that became a moral testament:

How good it is that I do not fear death,

nor ask if my cross is heavy.

That before you, my judges, I do not bow

in anticipation of unknown miles.

That I lived, I loved, and kept myself unstained,

free of hatred, curses, and repentance.

My people, I shall return to you once more,

and in death I shall rise into life…

Recognition and legacy

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Vasyl Stus was posthumously rehabilitated. In 2005, he was awarded the title Hero of Ukraine. His name has since become synonymous with the struggle for freedom of expression and human dignity.

Today, his memory lives not only in schoolbooks and official memorials but also in poetry readings, cultural events, and online initiatives. The Stus Center in Ukraine preserves and digitizes his works, ensuring that future generations encounter the voice of a poet who refused to be silenced.

The Virtual Museum of Political Repressions “Perm-36” continues its work despite difficult circumstances, preserving the memory of Stus and of all those who suffered or died for their beliefs. On the 40th anniversary of his death, Ukraine and many countries abroad hold readings of his poetry, exhibitions, and lectures on the dissident movement.

The enduring voice

Vasyl Stus remains a vital example of how courage and the written word can stand against a repressive system — even when the price is life itself. His poems continue to speak for him: a voice that could not be silenced.

“Forbidden” — a feature film about Vasyl Stus (2019).