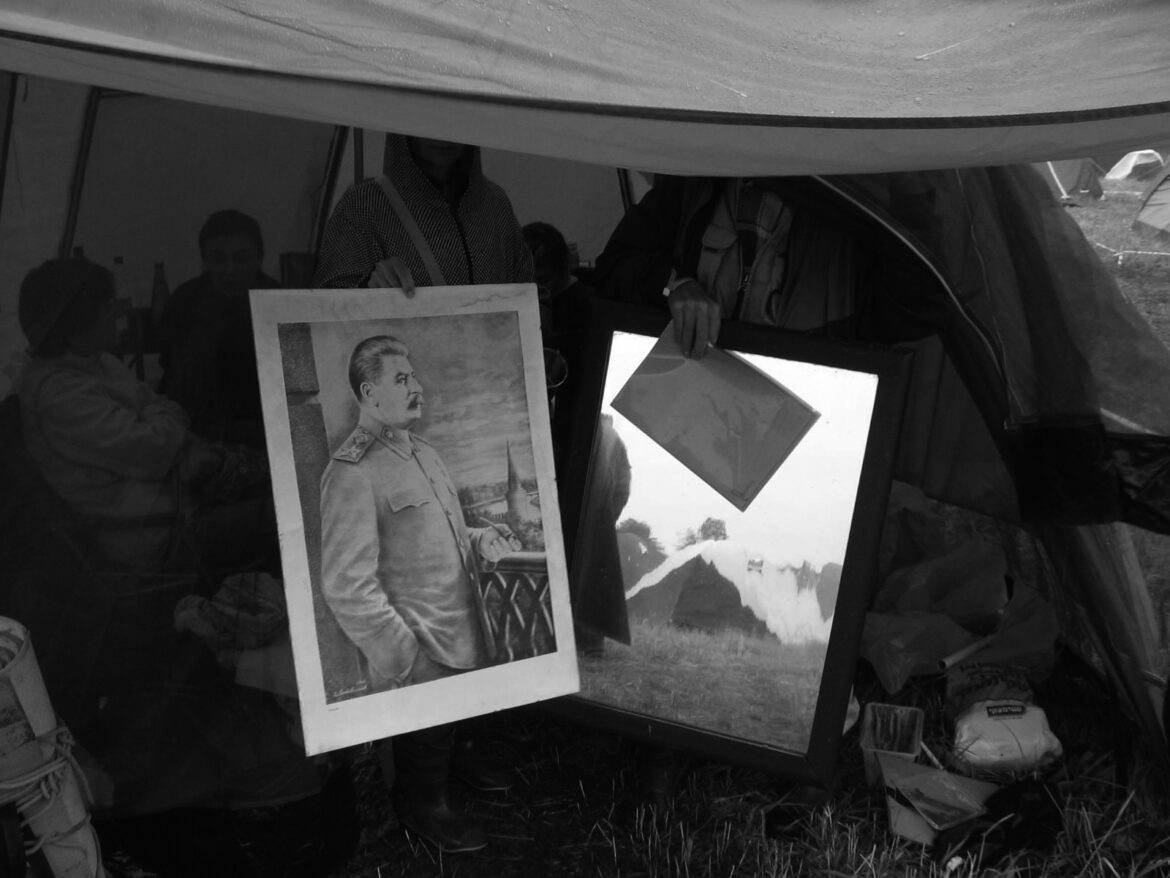

…This mirror always hung at our dacha in the village of Bykovka. Not in that Bykovka, where Viktor Astafiev wrote “The Shepherdess and the Shepherd,” but in another one – the new Bykovka, which is five kilometers away. True, they say that the house my parents bought almost half a century ago – a large, sound house – was once moved here from the old Bykivka. When the timber industry enterprise that had already mastered the whole territory there moved there. They dismantled it log by log and transported it.

For at least twenty years this mirror was hanging. I remember, because I hung it up myself. Admittedly, it hung in a rather awkward place, in such a narrow alleyway, and opposite a window, through which the sun sometimes peeked in at night. So it was uncomfortable to look into the mirror, and besides, it was old and dull, with touched by time amalgam.

In general, it hung and hung, performing at best its functions, and then fell down. It seemed to have jumped off a carelessly hammered in wall nail. But it did not break.

When I undertook to repair the old mirror and removed the rail holding the heavy glass, he looked at me…

When I realized that all this time, all these twenty years, perhaps even more, he was looking at me, at my parents (they told me how they wept so sincerely in 1953), at my growing daughters, at my two uncles, World War II veterans (they are long dead), at numerous guests who came here…

Where did he come from, how did he find himself in my house as an uninvited guest? Maybe it used to belong to my aunt, who died twenty-five years ago, after which her belongings were partially evacuated to this dacha? I remember that before she retired, she was a police major. True, from all the surviving photos she looks at me in a captain’s uniform, apparently she was retired as a major. She participated in the war, too – as a very young girl. She was thrown to the rear of the Germans somewhere near Moscow. By parachute, like Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya. She never talked about it herself, one of her relatives told me, but without details. And I probably made up the story of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya myself. My aunt never had a family of her own, and she did not outlive her parents by much.

– Not in the police, but in the KGB,” my mother corrected me. – Then she left with a scandal. Or rather, she was fired for something, and was reinstated through the courts. No, what kind of court – through the ministry. But after that she refused to work in state security and joined the police.

Well, yes, if she went to the rear of the Germans, it was probably not the militia – how come I did not think of it myself.

– But it is hardly your aunt’s mirror, – my mother hounded me again. – I think we inherited it from the previous owners along with the house. The head of the family worked at the timber processing plant, was a communist, a veteran, an award-winning worker, I think, even a people’s assessor at the district court.

So? After ’53, or rather after the XXth congress of the party, when the idol was thrown down from its pedestals, the previous owner of the house decided to keep it at least in this unusual way? Or maybe he thought that if the “real master” came back… Or maybe, while shaving in the morning, he talked to the chief and the teacher…?

Who knows. The twists and turns of history are enigmatic. When we came here, the master of the house had long since passed away. Maybe he got the mirror by accident, and he had no idea who was watching him and the world, grinning with a mustache.

What can we do, our history still wanders in the dark.

I gave this mirror to Viktor Shmyrov, one of the founders and director of the “Perm 36” museum, at the end of July 2011. During the International Forum “Pilorama”.

– Good exhibit,” Shmyrov said, accepting the unexpected gift.

The publication is taken from Perm News, by Andrei Nikitin

At the moment the fate of this exhibit is unknown.